HAR KARKOM

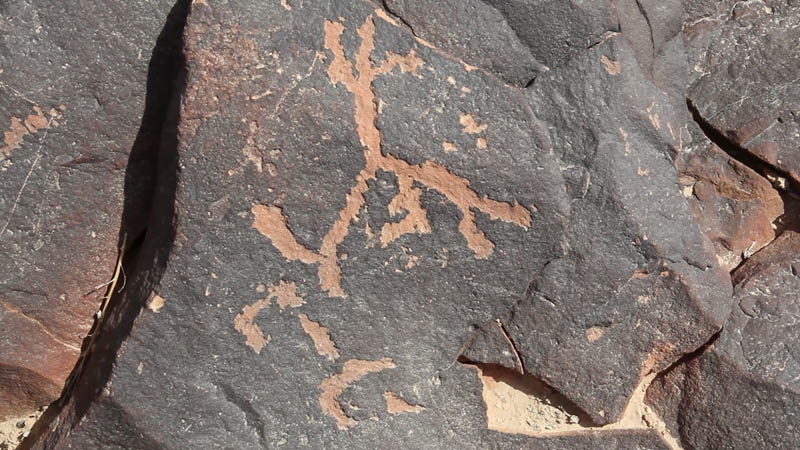

The Y (yad) is a separate arm; the arms and head of H (which will become E in the Greek and Roman alphabets, when the body has been discarded) are at the bottom, and the H figure is sometimes found upside down (standing on his hands) in other places, in the Bronze Age, and one slanting leg stands for both; and so the o- is W, a nail (waw), producing the name YHW.

The next one (HK3d) apparently has the same word YHW, with the person's arms and head below and the single leg above for H, and the Waw (o---) crossing the body, and the Yad-arm on the left or right of this combination

Here is yet another from the same sequence of marker-stones (HK3a), which would also say YHW (the arm has a hand but the H is not tidy, having one arm up and the other down); alternatively the single stroke might be an arm (Y), the middle character a simplified exulter (H), and a hook (W), hence YHW (Yahwe):-

From a different site (HK15b) we see a mysterious conglomeration of signs: Y (arm, a short stroke) H (exulter) W, as a monogram of YHW (Yahwe); the marks below might be a single letter H (or perhaps an ox-head and a crook, 'L, El, God):-

A few inscriptions have an additional H, and this could stand for the masculine pronoun "he" (hu), hence "He is Yahu"; or it could be functioning as the whole word HLL (without the vowels); thus it would be saying Hallelu Yah! However, YHH is known as a form of the divine name in the Aramaic documents of the Jewish community of Elephantine in southern Egypt, in the 5th century BCE. We find YH and YHW and YHWH in the Bible, but not YHH.

https://www.academia.edu/45386848/KUNTILLET_%CA%BFAJRUD_PILGRIM_S_ROADHOUSE_TO_MOUNT_SINAI_HAR_KARKOM_?email_work_card=title

https://negevrockart.co.il/

MOUNT EBAL

On a higher eminence in Israel, namely Mount Ebal, the twin of Mount Gerizim, near the ancient city Shekem (Shechem, now Nablus), a small document made of lead, with inscriptions engraved on it, has been excavated, and the divine name YHW appears (apparently!) in its minuscule text.

https://cryptcracker.blogspot.com/2023/12/ebal-curse-tablet.html

In

this thesis-summary (May 20, 2025, Appendix 2, 173-181) Michael S.

Bar-Ron (supported by Pieter Gert van der Veen and Walter Mattfeld),

makes a case for identifying these two mountains as the original Mount

Sinai and Mount Horeb, since one of them is Jebel Saniyah and the other

is Jebel Ghorabi, and this certainly invites us to pause and ponder.

Notice in passing some confusion in the presentation of the evidence: on page 174, the name appears as Ghorabi, but also as Ghoriba, and the caption to the picture on page 181, reproduced above, has "Jebel Saniyah and Ghroiba

from Serabit el-Khadim". We are looking at one of the Sinai turquoise

mines, in the foreground, and this region has yielded a host of

proto-alphabetic inscriptions, which I have been studying intensely

throughout my long life, in my search for the origin of the alphabet.

https://www.academia.edu/12894458/The_origin_of_the_alphabet

Ronald Stewart (on his Academia page) rejects an Arabian Horeb in favour of Jabal Musa in Sinai, and also takes up the twin peak idea. The plain at that site is part of the case for Israel having camped there.

Michael Bar-Ron rejects Jabal Maqla/Jabal Safsafa in Arabia, as having a very weak case; but he is unaware of the stupendous inscriptional evidence that is available to prove that this is the most likely "mountain of God" from which YHW spoke.

However, this place has inscriptions that include the divine name YHW. Ron Van Brenk in Canada has highlighted the important graffiti that have survived in this area, and he argues that they testify to the presence of the children of Israel, who had migrated here after their exodus from Egypt. He points to a niche in the rock-face where Moses could have sat in judgement (Ex 18:13); and a location for an altar for the "golden calf" episode (Ex 32:1-6).

In approaching ancient inscriptions we must always keep in mind that the writers knew what the intended meanings were, but we are prone to misinterpret them. Van Brenk has made valiant attempts to interpret the inscriptions, but I will transcribe and translate them in accordance with my paradigm of signs and sounds of the West Semitic "Quadrinity", the four forms of the Proto-alphabet in the Bronze Age.

https://cryptcracker.blogspot.com/2021/04/another-lakish-inscription.html

This is embedded in :the "petroglyph panel", which depicts an assortment of animals and humans.

Photographs are from Ron Van Brenk's presentation of the document.

https://www.academia.edu/100674894/The_Petroglyph_Panel

Here is a relevant extract:

"Living YHW"

YHWH is a "living God, speaking out of the fire" (Deuteronomy 5:23); "a living God in in your midst", (Joshua 3:10)

"YHWH is alive" (Psalm 18:47, Samuel 22:47).

H is a stick figure of a person rejoicing (>-E).

W is a circle on a stem, representing waw, nail (--o).

H. (Hh, H.et) is a mansion with a round courtyard, h.az.ir (in proper conventional transcription, the dot I am placing after a letter will be positioned under it!).

However, if the figure to the left of the H.Y is a cross, and thus T (taw, mark, signature), then the word H.YT emerges, meaning "animals", and so "YHW of animals", or "YHW and animals", if the Waw is having a double function.

Furthermore, to the right of the YHW is a bovine head (with horns and an eye) for 'Alep, and a rejoicing human for H, and a tiny Waw, perhaps producing 'HW, which could be the Bronze Age form of Hebrew 'ehye, saying "I am". Looking at the sentence literally, we see "I am he is living".

At this point we may think of the theophany that Moses experienced at a mountain in the land of Midian (as this one is) when he was with flocks, and conversed with the great God named 'I AM" (Exodus 3:14).

Now, although a reading "I am YHW" may be a consummation devoutly to be wished, I must ponder whether this is what the writer intended. The 'Alep I am invoking is merely the horns of one of the beasts, facing left towards the small human I am relying on for the aspiration in 'HW; the same sort of horns are on another large animal, facing right towards a human figure. The He for YHW is not upright, and it could be a quadruped.

Possibly this is a Stone-Age work, and a Bronze-Age artist or scribe has cryptically inserted some written words into the picture, possibly "YHW alive" or "YHW and animals", but it may be only an amazing coincidence that has sparked the imagination of this viewer, to see things that are not there.

(2) Rock inscription 'HW YHW 'LHK

https://www.academia.edu/123774718/A_Pictograph_Mt_Sinai

My proposal is that these two monograms say:

"I am YHW "

Next, both have a Waw (o--) crossing their middle line. This combination would produce the sequence HW. The larger image has a circular head, and upraised forearms and hands; the one on the left has a bovine head, which could represent the glottal-stop letter 'Alep, and combine with HW to produce the word I was seeking on the animal tableau, 'HW, "I am".

The other collection of signs would serendipitously provide YHW, "he is", and thus the divine name YHW, if I could find a Yod. On the far right (above a trace of Ron's hair, which indicates his former presence in this photograph) is a short vertical stroke which might be part of a character depicting forearm and hand (=|), but it is rather remote. Below the hand on the right side (the left hand, presumably) is a diagonal mark which could readily serve as a Yod (elbow, forearm, hand); but the other hand seems to have an eroded line running down from it to the head of the Waw. So I accept that we have now established this sequence: 'HW YHW, "I am YHW".

'HW YHW 'LHK "I am YHW thy God".

Compare this with the beginning of the Ten Commandments document (Exodus 20:2):

That weather-worn splatter must have been a legible text originally. Perhaps it said:

"I am YHW thy God, who brought thee out of the land of Egypt, away from the home of slaves. Thou shalt have no other gods beside me" (20:2-3).

(Coincidentally, in the essay that Ron Van Brenk has devoted to these stupendous pictures, "A Pictograph @ Mt. Sinai: The Very First Commandment", he relates this inscription to the "no other gods" injunction, but he fails to see that this is writing, not pictures, and the two clusters of letters are monograms, not pictographs.)

When Moses asks God what name he shall tell to his people, "God said to Moses, I AM THAT I AM ('HYH 'ShR 'HYH) ... say I AM has sent me to you" (3:14). Subsequently, "I am YHWH", who appeared to the forefathers "as 'El Shadday, but by my name YHWH I was not known to them" (6:2-3).

And here now is a mountain that was associated with the name YHW, and it is in a part of Arabia that was anciently the land of Midian, where Moses took refuge for many years (2:15-16, 3:1-2, 4:19).

(3) Statute stones YHW 'LHN

https://www.academia.edu/126795857/The_Third_Commandment_Observed_our_earliest_YHWH_discovered_to_date_

They are not the two stone tablets on which the Law of YHW was engraved, but there is a reference to that lawcode in the text, which is addressed to YHW. The sentence begins with the name YHW and continues in boustrophedon fashion (top line sinistrograde, L<-R, bottom line dextrograde, L->R). However, there are actually five lines proceeding in alternating directions (boustrophedon, "as an ox turns in ploughing").

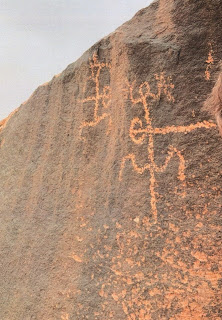

We begin here:

The second character is an unusual form of He; not a stick figure, but a complete image of a person with arms raised in jubilation.

The next sign is a blob but the nail of Waw (--o) is discernible.

So we have YHW (the H of the four-letter Tetragrammaton YHWH was added later in time as an indication of a vowel, a or e).

Now, there is another set of signs running parallel with YHW, but in the opposite direction.

First find the 'Alep, the ox-head with two horns, a much fainter image; its snout is pointing to its accompanying characters.

Below it is a crook, for L /l/; it is lying horizontally with its hook at the right-hand end of the staff (detected with imagination on the large image of this photograph on my big screen).

Next is a jubilating person, again for H, but not upright, though not upside down, a stance that sometimes occurs.

And then I would expect a wavy M, and I think that is possible, yielding the word 'LHM ('elohim), and we are thus addressing "Yahwe God".

However, I think it might be a cobra, and so N, producing 'LHN ('elohenu), "our God".

Returning to the top line (the section now recognized as line 3), in fourth position from the right is the mansion-sign for /h./.

Then Qaw, "measuring line", a cord wound on a stick (--o-), sometimes with the end of the string poking out, and that is what we see here, but the circle of the cord has faded.

The last letter in this top line is K, a hand (kap) depicted with three fingers.

H.Q could be h.oq, "statute, law", and K is -ka, 2nd person suffix, thus producing:

"Thy law".

The first letter on the left of the lower line (line 4) is H, it is a hank of thread (hayt.) in the form of a double helix. The presence of these two consonantograms (H. and H) in this inscription shows that the script is the "Protoconsonantary" (the original longer version of the proto-alphabet) since these two letters were omitted from the Neoconsonantary (reduced to 22 letters).

Next we have a character made of two parallel strokes, to be identified as D (Dh, as in "this", which should be written as "dhis", in dhis thing). Dhis is another indicator of the Protoconsonantary.

Now another Q (Qaw, cord wound on a stick); the identification of this letter was an original discovery of mine (1990) but it is heartlessly rejected or blithely ignored by the other scholars in this field.

This sequence provides us with the West Semitic root H.ZQ, but as older HDQ, "be strong". This could be the adjective, "powerful".

YHW our God, thy law is powerful

The following letter is B (bayt) "house".

The last letter in the line is unclear, but I take it to be another bovine head with horns: 'Alep.

The final letter of the text has the bottom line (line 5) to itself; it is a sun-symbol, with two serpents, one on each side; it goes with the word shimsh, "sun", and represents Sh; yet again the establishmentarians have thrust my identification aside.

The sequence that emerges is B'Sh. There is such a root, but it means bad, rotten. If the B is the preposition, basically meaning "in", then 'Sh could be "fire" or "man".

YHW God, thy law is powerful in a man.

YHW God, thy law is powerful in/as fire.

"Is not my word like fire, says YHWH"(Jeremiah 23:29)

"You came near and stood below the mountain; and the mountain burned with fire ... and YHWH spoke to you out of the fire ... and he declared to you his covenant ... the Ten Words, and he wrote them on two stone tablets; and YHWH commanded me at that time to teach you statutes and judgements". And to covenant-breakers "YHWH thy God is a consuming fire" (Deuteronomy 4:11-14, 24). The word "statutes" is h.uqqim, as in H.QK, "thy law" in this inscription.

The letters on another stone are a hand and a H.et, and as KH. they render the Hebrew word koh., meaning "power"; this reading is not certain, but "power" certainly fits with the word "powerful" in the other text, and it may be a heading or a summary. Actually, the white stroke might be another letter, as the stem of a Q, but it could be the wrist of the hand; the orange line higher up has a wound cord, with its upper stem and protruding string (look carefully for these details), and this familiar combination produces H.QK, "Thy Law".

There is a field of stones at this site, and I am waiting for Ron Van Brenk and others to bring more inscriptions to light.

Meanwhile, here is something surprising with which I have been personally involved.

(4) Menorah of YHW 'LHM

The complete picture is available in the first minute of the testimony of Sung Hak Kim:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KfGauUpw87w

This is an inscription that I was personally involved with, as the man who discovered it sent pictures of it to me. and asked for my opinion. I accept that this is a drawing of a menora (lampstand, with seven branches, as in the Tabernacle, Exodus. 25:31-40). At that time I was overawed by all the Arabic writing, and I did not notice the proto-alphabetic letters accompanying it: Y (forearm with hand) H (person exulting) 'Alep (ox-head) L (crook). This could be read as Yahu 'El, "Yahu God". However, I think there is a Waw above the H, and below the L is another H, hence 'LH "God"; and if a Mem is lurking there (and I can see two possible candidates), it would make YHWH 'LHM, "YHWH God". This set of marks would have bee n placed there in the Bronze Age, and the Arabian alphabetic writing came later.

(5) Eyes of YHW

Another view of this artefact is accessible at 45.30 in the Testimony of Sung Hak Kim

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KfGauUpw87w

A photograph of this object (from the Jabal al-Lawz area) was sent to me by Brad Sparks in 2009, and I ventured to say that the divine name might be present on the rear of the stone; if so, it seems strange to find it on a "graven image" of a bearded male. The clear exulting figure is a Bronze-Age H, with a Waw next to it on the left. Where is the expected Yad arm? Possibly it is obscured in the bottom right corner; or the hand is there (notice two parallel lines), and the forearm is a line made by the surviving marks running along the edge. This is apparently a circular text, and there is a letter at bottom centre, possibly a sun-sign, Sh, "of". On the left side at the top. the dot might be the pupil of an eye, with its upper and lower eyelids (arcs, not a circle) faintly surviving. Below it there is perhaps a snake, hence `N, "eye" or "eyes", and thus: `N Sh YHW, "The eyes of YHW" (as depicted on the face: large and denoting "all-seeing eyes").

The two letters on the face could be a short version of Yad (representing hand and wrist only, as on the Menorah inscription, 6 above), and in combination with H denoting Yahu (though there might be a Waw squeezed in between the the H and the nose, but the writer's intention remains obscure.

At this point (even if the proposed readings are faulty) we shall note some connections between these "phenomena" and related Biblical ideas about "The eyes of YHWH".

In Deuteronomy (11:11-12) Moses speaks about the promised land: "it drinks water by the rain from heaven, a land which YHWH thy God cares for; the eyes of YHWH thy God are always upon it".

The term "YHWH thy God" (as YHW 'LHK) appeared in the rock inscription (2).

King Hezekiah implores God thus: "... open thine eyes, O YHWH, and see and hear the words of Sennacherib, which he has sent to mock the living God" (Isaiah 37:17).

Compare "the living YHWH" in the rock tableau (1).

Moses speaks to Israel about "heeding the voice of YHWH thy God, keeping all his commandments ... doing what is right in the eyes of YHWH thy God" (Deuteronomy13:19).

YHWH is intent on slaying his people for their waywardness: "I will set my eyes upon them for evil and not for good.... Did I not bring Israel from the land of Egypt? ... Behold, the eyes of the Lord YHWH are against the sinful kingdom" (Amos 9:4-8).

Notice this mention of the Exodus as having happened under the watchful eyes of YHWH,

In a vision the prophet Zechariah sees a menora: "a lanpstand all of gold ... with seven lamps on it" (4:2); "and "these seven are the eyes of YHWH, which range through the whole earth" (4:10).

This makes a nice connection between the drawing of the lampstand (4) and the eyes of YHW (5).

(6) Agents of YHW

https://www.ancientpages.com/2019/11/21/ancient-hebrew-inscription-reveals-location-of-biblical-mount-sinai/

This is my rough sketch (meely to assist in locating details) and a photograph of a rock tableau that is shown in Ryan Mauro's

presentation of the evidence from Jabal Maqla (at 18.04 of 24.50). He included it because it is one of several examples of a drawing of a footprint, presumed to indicate ownership of the land; but in this instance the bare foot to the right of the group of five persons might mark this place as holy, and footwear should be removed, as Moses did when "he came to the mountain of God, to Horeb", because he was standing on "holy ground" (Exodus 3:1-5). Also the campsite had to be kept ritually clean, as YHWH was present, "so your camp must be holy" (Deuteronomy 23:9-14).

Actually, the word QDSh ("holy") appears to the right of the foot: Q is a "line" (qaw), a cord wound on a stick, with two projecting strokes at the top; D is a door (dalt) in a horizontal stance, with its post at the top, and it has two panels; Sh is a symbol of the sun (shimsh), consisting of the solar disc with a serpent on each side, obliquely below the door.

For the discussion of this panel, the reader needs to click once on

the photograph to enlarge it, and then either make a copy of it on

paper, or have it beside the text on the computer screen.

In the top left corner of the picture, the large arm says Y (yad); and the exulting character is H, of course; a W o-- (waw) is there, to the left of the feet of the H, and that would make another YHW.

In the space creaed by these three letters, a round head is perhaps detectable, with facial features,

To the right of the divine name there are human figures and many marks that could be writing.

The person on the left seems to be holding a rod in his right hand; there is a large eye with pupil next to it; below this presumed `ayin is a sun-sign with two serpents for Sh; and then H, a very tall stick-figure, producing the name HSh`(Hoshea`) who was given the YHW-name Yehoshua`by Moses (Numbers 13:8,

16), and he was apparently the first descendant of Jacob-Israel to have a

YHW-name).

At the bottom I see an ox-head, a jubilater, a human head, and a snake, and this could be 'HRN, the signature of Aharon (Aaron) the High Priest, who is depicted here with his bejeweled breastplate (Exodus 23:15-30, 39:8-21, with 12 different jewels, inscribed with the names of the tribes of Israel, and arranged in 4 rows of 3 gems, and a gold ring at each corner); close inspection of the photograph indeed reveals four rows of three dots; in one hand he is holding a censer, for making an offering of incense (Numbers 16:41-50, Hebrew text 17:6-15), and in the other hand he is wielding his rod (Numbers 17:1-11, Hebrew text 17:16-26). Incidentally, Aaron's rod was from an almond tree (shaqed), and the Arabic word lawz, as in Jabal al-Lawz, means "almond". Is this coincidence or connection?

To the right of the third man is a vertical wavy line and a sun-sign, and this would yield MSh, Moshe, Moses. An accompanying snake denotes N, and a house says B, and NB would be nabi', "prophet" (Deuteronmy 34:10).

The man in the middle is H.R, another associate of Moses (Exodus 17:10, 24:14). Rabbinic tradition has H,ur as a son of Caleb and Miriam (The New Bible Dictionary, 1962, 831). He only appears in these two instances, and then disappears (unless he changed his name and neglected to tell us).

This company of men are all registered as being engaged in the battle against `Amaleq (Exodus 17).

Miryam is also here, with her timbrel (Exodus 15:20), and her signature, MRYM.

All these Bible characters have suddenly become authentic historical personages.

Denial of Moses and the Exodus is no longer an option.

In the presence of all this evidence we now know that Moshe wrote early Israelian Hebraic language with the full proto-alphabet, the Proto-consonantary constructed out of the West Semitic Proto-syllabary by his ancestors, Ya`qob and sons.

In this regard, standing between the W and H of YHW is a person who seems to be holding two tablets.

Who might the artist be? After YHW, the most prominent name is HSh`, writ large forsooth: the 'ayin eye is enormous; the solar disc for Sh is a big circle with a centre-dot (as in Egyptian hieroglyphs); the exulting stick-man is taller than the portrait of Hoshea`. Also, I think we can allow a long arm to emanate from the foot of the H-figure, with a hand at the end. I had thought that the hand might be a snake to provide N for the word KHN, "priest", to accompany the name `HRN, Aharon; there is a K-hand with fingers, then a little H-figure with a dot-head, and the required N runs up alongside the stem of the Waw of YHW.

Thus, Yehoshua` has positioned his unique YHW name, and his self-portrait, right next to the sacred name, which he has written with huge letters. If we demand to see his credentials, we find this: "Yehoshua` made a covenant with the people that day, and set them a statute (h,oq) and a judgement (mishpat.) in Shekem, and wrote these words in a book of the instruction (tora) of God; and he took a great stone and set it up there ... a witness ... of all the words of YHW ..." (Joshua 24:25-27).

Notice the word "statute (h,oq) as seen in the inscriptions on stone in section 3 above. Can we attribute them also to Yehoshua`?

But here comes another stone-panel where we see the same happy company of Exodus leaders.

(7) Historical Personages

This tableau depicts a variety of animals, including four human stick-figures, three male and one female, according to Ron Van Brenk, who has published this picture (p.12 of 57)

https://www.academia.edu/100674894/The_Petroglyph_Panel

In the light of the evidence gleaned from the preceding panel, we may ask whether Miriam is the woman, and above her Moses, Aaron, and Joshua. When this photograph is viewed on a full computer screen (click once to enlarge it), no writing is detectable, though there are possibly some letters on the stone all around it, and also some robust humans.

Surprisingly, on the upper right side of the rock there is an image that seems to portray a woman with a timbrel, and indeede the name Miryam (apparently) appears under her feet, as a monogram: MRYM (water head arm water). In the Bible Miryam is identified as a prophetess and sister of Aharon (Exodus 15:20), and sister of Aharon and of Moshe (Numbers 26:59).

Aharon is at bottom right; he has his breastplate beside him (note the jewels, represented by dots).

Moshe could be the imposing personage on the left side (though it could be an image of YHW, who is said to have a visible form, Exodus 33:21-23). The words for "the prophet Moshe" (NB MSh) as on the other Panel (6) are perhaps discernible above the head of this figure.

Hoshea` alias Yehoshua`is presumably the remaining figure.

"God alone knows the truth."

(8) YHW

Looking first at the two obvious letters (on the dark-coloured stone), the upper glyph is Y (an arm, yad, not a boomerang, gaml, G), and the lower one is H (noting that head of the ecstatic leaper has faded), and the expected W (o--) is to the left of the legs (click to enlarge). Looking at the large version of the picture, you will see Aharon with his breastplate, replete with dots representing gems (as noted already on 6 and 7 above).

Moshe would be expected to be present, and the next set of coloured lines forms a tall figure, who may be holding some tablets. And beyond that two more individuala, possibly Yehoshua` and Miryam.

There are more marks on both stones awaiting interpretation.

(9) Midian YHW

This inscription might be read as YHW'LHM equivalent to Hebraic Yahwe 'Elohim, "Yahwe God".

It is visible on a stone in "the caves of Jethro" at al-Bad' in the ancient land of Midian, and this seems to indicate that the people of that area worshiped YHW.

I have copied the letters from picture No 52 at the website "Mount Sinai - A selection of images".

Moses was living in the land of Midian in Arabia, and with the flock belonging to his father-in-law Jethro he came to the mountain of revelation (the one with the burning bush); he was told by God that he was to bring the people Israel to this very mountain (Exodus 3:12), It is unlikely that Moses had taken the animals to a place in the Sinai Peninsula on that occasion.

The presence of so many YHW inscriptions at this location seems to confirm its identity as the special mountain of YHW God.

But as they moved around in their nomadic wanderings in Arabia and Sinai, they may have communed with YHW (who was leading them) at other mountains.

However, Jabal Maqla has many instances of the name YHW and a reference to the law of YHW, and a menora, and a congregation of famous children of Israel (pictured and named) and all these distinguishing features are unique and cogent.

By the way, when Moses went to Midian, he did not have to cross the Red

Sea, and likewise when Aaron visited him; there were land routes

to Arabia. The crossing of the Yam Suph ("Reed Sea") would probably have

taken place somewhere in Egypt. However, the position on the Red Sea

that is proposed by many scholars as the locus of the miracle may have

also been a regular ferrying place, though it would be a long journey

instead of a short voyage if a passageway was opened up. But Baal-Saphon

would surely have been in Egypt, and the Sea that barred the way to

Israel would have had reeds in prominence, and would be one of the great

lakes in the Suez Canal region. The Bible does not distinguish inland seas from open seas.

The Exodus route included two encounters with a Yam Suph. First, the sea that was crossed miraculously: it is merely referred to as "the sea" in Exodus 14, but it was Yam Suph that they departed from to enter the wilderness of Shur (15:22); then to Elim, and subsequently to "the wilderness of Sin which is between Elim and Sinai" (16:1). Another source (Numbers 33:10-15) says that after Elim they camped by the Reed Sea, then moved to the wilderness of Sin, and then Dophkah (which is considered to be a good candidate for being Serabit el-Khadim, where turquoise and copper were mined, and the Saniya and Ghoriba mountains stood); next came Alush and Rephidim, and the wilderness of Sinai.

In the light of all the supporting evidence for Jabal Maqlah in NW Arabia as Mount Sinai alias Horeb, the wilderness of Sinai must have been this area, and not a region in the Sinai Peninsula; but the Sin wilderness could have been in Sinai.

And the name Yam Suph may have been applied to all the waters associated with the Suez Canal, including the Red Sea on the Gulf of Suez.

(10) YHW Abroad

This is part of an ancient panel, and we can find YHW in the bottom-right area (above a woolly sheep?).

Begin with H (the jubilant person is doing hand-stands). This stance is known from the Sinai proto-alphabetic inscription 358, where it is the pronoun suffix -h, "his", in "'Asi has done his work" (one of the four 's inscriptions, which I take as referring to Asriel, a son of Manasseh by his Aramean concubine, Numbers 26:3, 1 Chronicles 7:14). This inverted H also appears on the Lakish ivory lice comb.

W (upright o--) is to the left of H.

Y is the forked stick character next to them, which has a hand, a forearm, and a short angle-elbow.

Could the personage with outstretched arms and prominent eyes be YHW?

No, it is Aaron ('Aharon) wearing his priestly breastplate (the dots represent jewels, as in 6, 7, 8 above).

To the left, apparently, is a menora (seven-branched lampstand, see 4 above), but it seems to have two rows of lamps, which are entangled, so to speak, in the horns of an animal.

His name is below him on the bottom line: an ox-head, 'Alep, an upright H, a human head, R, snake N : 'HRN

His sister Miriam is standing beside him, with her drum and stick.

Is Moses represented as a newly born baby (centre right), with his mother, and two onlookers?

And again, far left, there is a man holding a tablet, or two: a vertical stream of writing has "Moses the prophet": M (with four waves), and Sh with a sun-disc and a serpent on either side; and a snake and a house, for NB (nabi' "prophet", as in 6 above).

Rochester B (right side)

Click to enlarge and make a copy

Perhaps it is Moses and the burning bush, with the Angel of YHWH:

"Moshe was tending the flock of Yitro, his father-in-law, priest of Midian, and he led the flock to the far side of the wilderness, and he came to the mountain of 'Elohim, to Horeb; and the Angel of YHWH appeared to him in a flame of fire from the midst of a bush" (Exodus 3:1-2a).

The sequence M Sh N B extends from him to the head of a larger figure with arms outstretched

Q --o< (upright), D door (next to it), Sh sun with two serpents.

Also, apparently, above the left side of the eightfold arc.

The surprise is that this occurrence of "YHW" and "Moses the

prophet" is well and truly "abroad", as it is found at a sacred site in

Utah, on a Rochester panel, one of "13 panels of Barrier Canyon- and

Fremont-style petroglyphs and pictographs".

(National Geographic 245, 05, 84-107, "Storied Rock"). The petroglyphs are considered to be thousands of years old.

Archaeologists of the Navajo Nation (reported in the caption below the

picture) interpret the arch as a rainbow, and they naturally think of

rain-making as the purpose of the tableau, in the arid environment.

I now propose that this is the mountain of God, perhaps with flames at the top, though falling rain is also possible.

https://www.utahsadventurefamily.com/mcconkie-ranch-petroglyphs/

https://cryptcracker.blogspot.

encountered Caribbean islands before reaching America, as did Columbus..

https://sites.google.com/view/

and his name is M (water) Sh (sun-disc with two serpents), Moshe.

thrice at Mount Sinai in Arabia, twice in Utah, USA, and now here in Jamaica.

https://cryptcracker.blogspot.

So far, the writing has been the Proto-consonantary (the consonantal Proto-alphabet with no indication of vowels).

The name YHW is here written in syllabograms, YA-HA-WI.

HA is the same as the first letter in the the inscription above it, a temple, haykal;

This could have been the work of members of the seafaring tribes of Israel, after they had settled into the land of Kana`an, and had resumed the international merchant shipping activity that they had performed at Avaris in Goshen. Utah is closer to the Pacific Ocean than to the Atlantic Ocean, but Texas had a gold mine with proto-alphabetic writing, and the family of Israel owned that script. The assumption is that familiarity with YHW only arose at the time of the Exodus in the Late Bronze Age, and this is Bronze-Age writing, not the Phoenician alphabet of the Iron Age.

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1QATcj_MTlGa5cZzO8sQnzR5lBw8lPTWT/view

HW%20Face.jpeg)

HW.jpeg)