First published here:

The version offered here is being modified:

I feel like the woman in the parable (Luke 15:8-9) who lit a lamp, poured light on the scene, and searched diligently for a lost coin, one of her ten silver drachmas; when she found it she rejoiced and rushed to tell her friends and neighbours. So here is my ten drachmas’ worth to share with everybody, as I feel that I have alighted on something significant that has been overlooked for three millennia. This lost object, now ready for our inspection, is just one of a whole bunch of keys that can open doors to our understanding of the early alphabet, with regard to its features and functions. Indeed, it is a missing link in a ten-point theory of the origin and evolution of the alphabet.

The main difficulty we encounter, as practitioners of ancient Hebrew epigraphy, is the dearth of documents available, from those early centuries of the Iron Age. The few inscriptions we do have are brief and frequently fragmentary.[1] However, things are now improving, and we possess two five-line texts, namely the Izbet Sartah Ostracon[2] and the Khirbet Qeiyafa Ostracon[3].

The Qeiyafa Ostracon came to light in Khirbet Qeiyafa, a fort overlooking the Valley of Elah, where David confronted Goliath (1 Samuel 17); the site has been plausibly identified as Sha`arayim (mentioned in 1 Samuel 17:52).

https://sites.google.com/view/collesseum/qeiyafa-ostracon-2

The question that begs to be asked (though nobody has dared to articulate it) is whether all the variations are arbitrary (just vagaries of the writer’s style of handwriting, like the three different renderings of P in my personal repertoire) or whether the differences are deliberate and meaningful.

The common assumption is that the early Hebrew alphabet was like the Phoenician alphabet of the Iron Age: it had twenty-two letters and each of them stood for a particular consonant, and of course there was no indication of the vowels in writing. The dots and dashes found in Hebrew Bibles for indicating vowels were much later inventions of scribes who were concerned that the Sacred Scriptures should be recited correctly. Eventually, later in the Iron Age, vowel markers were inserted in a Hebrew text, using Waw for showing the presence of a long u or o, Yod for long i or e, and He for long a; these are known technically as matres lectionis (mothers of reading, offering sustenance to the reader, so to speak). This idea was not used in Phoenician inscriptions, but it is still employed in Modern Hebrew writing.

Returning to our question regarding the possible significance of the variations in the letters on the Qeiyafa Ostracon, we may now ask whether the various forms and stances of each letter constituted a way of denoting particular vowels. Actually, there was already an analogy for this in the West Semitic cuneiform alphabet, which was particularly associated with the city of Ugarit (on the Syrian coast, east of Cyprus) but it is also attested throughout the Levant. The scribes of Ugarit, in the Late Bronze Age II, immediately preceding the Iron Age, had a cuneiform sign for each consonant, made up of wedge-shaped marks, and I think (having demonstrated this elsewhere) that almost all of them were constructed with the image of the corresponding letter of the Semitic alphabet in mind.[4] The relevant detail is this: on the clay tablets of Ugarit there were three distinct ’Aleph characters, representing ’a, ’i, ’u.

This phenomenon could have a connection with the trio of ’Aleph forms on the Qeiyafa Ostracon. But my idea goes further than that: in the early “Israelian” Hebrew alphabet each of its twenty-two letters had two additional forms, making a total of sixty-six signs. In fact, the system was not a simple consonantary (which the Phoenician alphabet certainly was, in the Iron Age) but a syllabary. Incidentally, there has long been a discussion about the nature of the Phoenician alphabet, and whether it should be understood as a syllabary, with each sign standing for a consonant with any vowel; but that is a different matter. What I am proposing here is a syllabic alphabet.

How can this syllabary hypothesis be tested? A first step would be to compare the letters found on the Qeiyafa inscription with their counterparts in the Izbet Sartah text.

Habitually in this field of endeavour, the assumption is made that when the letters in this abecedary (or “abagadary”) are used in a text, the reader will have to supply the appropriate vowel in every case. However, in the four lines of writing above the Izbet Sartah alphabet (which are an interesting personal message from the writer himself, in my interpretation of them) we are offered Aleph in more than one stance (though the inverted A-form, the ox-head, is absent here). And when we have established the shape of the Lamed in the bottom line (more like a 6 than a 9), we look higher and see 9s as well as 6s (with the added complication that this scribe makes it difficult to distinguish B and L).

Consider also Kaph: we can see the origins of Greek Kappa in the model provided in line 5, but at the beginning of line 2 it is quite different, being a bisected right angle on a stem; I suggest (after experimenting with possible words and meanings in both texts) that the K-form says ka, and the trident is ki. My detailed observation of the letters in this line, in comparison with examples on the Qeiyafa inscription and other related documents, leads me to suspect that this inventory is indeed an abagadary, in which every sign has the vowel a built into it: ’A, BA, GA, DA, and so on to TA. The Taw here is not a simple + cross (like a plus sign) since the cross-beam points north-east; and if we focus on a trio of them, one above another, in lines 1, 2, and 4, we see the middle one has its cross-bar pointing north-west, and I have reasons for believing it is TI.

Now, if we take the Izbet Sartah TA to the Qeiyafa text, this matches the third letter in the top line, and the presumed TI is the penultimate sign in the bottom line. The TU is lurking in line 3 (a small character) as a cross that is shaped almost like a multiplication sign. If we apply this information to Phoenician inscriptions from the same period we might expect to see the TA syllabogram functioning as Taw, or even a perfectly even cross (+); but the TI is predominant.

Looking at Shin, we know two forms, “W” (SHI) and “3” (SHA in the Izbet Sartah abagadary); and the Qubur Walayda Bowl (pictured below) provides the third, a reversed “3”; the SHI sign (W) is what we see in the Phoenician realm, as well as in later Hebrew inscriptions, notably the Gezer Calendar [5], which show that the Phoenician style was adopted at some time in the 10th century BCE, the era of the reigns of David and Solomon, when commercial and diplomatic relations were flourishing between Jerusalem and Tyre.

A supposition is rising up before our eyes: the Izbet Sartah abagadary (with its a-vowel syllabograms) is not the place to look for the originals of the letters in the later consonantal alphabet, because this simpler system was made up of i-syllable signs (but with the vowels ignored). Fortunately we have at our disposal a list of the consonantal letters from Iron Age II, on the Tel Zayit Stone, and it seems that this document confirms the supposition.[6]

Thus, the Zayit K is not the KA of the Izbet Sartah abagadary, but the KI at the start of line 2 (as mentioned earlier), which is a trident. The Qeiyafa KI (at the end of line 4 in the word MLK “king”) apparently has no stem, but this is likewise the case with all the Phoenician examples.

Seeking a Phoenician counterpart for one of the three Aleph characters, we are at a loss, but perhaps the key feature is not the stance but the crossbar, which breaks through one side or both sides. The Zayit Aleph is typical, pointing leftwards, the direction of the writing, and having a vertical line cutting through it. However, we must acknowledge that the various scribes had their idiosyncrasies (whether regional or personal) and possibly made their own rules for distinguishing the syllabic forms of each letter.

Samek in the international consonantal alphabet was a “telegraph pole”, a stem with three (or just two) crossbars; it is actually an Egyptian djed, representing a spinal column. This character does not appear in any of the Iron Age I inscriptions, because they have a fish for their Samek. That is what we see in the Izbet Sartah abagadary between Nun and Pe; on the Qeiyafa text, in line 4, between Y and D (notice the dots indicating a fan-tail in each case); also on the Beth-Shemesh Ostracon; but prejudgement (rather than blind prejudice) does not allow most epigraphists to see it, because they are convinced that the fish in the Bronze Age proto-alphabet was D (from dag “fish”). Possibly the tree-shaped Samek functioned as SI in the syllabic alphabet, and it has not turned up in the extant inscriptions. There were presumably 66 signs, and we certainly have not seen them all yet.

‘Ayin in the Phoenician alphabet, as also on the Zayit Stone, is a circle, but without the centre-dot that is characteristic of the sign in the south in Iron Age I. However, on the Beth-Shemesh Ostracon [7] there is one of each, leading to the suspicion that the empty circle is the syllable ‘I. The sign for ‘U remains to be identified.

Mem has a variety of forms in the documents, but there are three basic types: the Phoenician M is presumably MI and it has the top stroke pointing NE, and the bottom stroke SW (the number of intervening angles varies for MI in Israel); MA has the top as NE and the bottom as SE (and only one angle in between); MU has the top as NW and the bottom as SW (with two angles or only one in between). Confusion could occur between MA and SHU, and also between SHA and short versions of MU, but the Sha-signs have horizontal tops and bottoms.

It should be emphasized that the letters in the Izbet Sartah abagadary are different from their counterparts in the Zayit alphabet, and this in itself supports the idea that the one gives the -a forms, and the other gives the -i forms acting as consonantal signs with no indication of its accompanying vowel. But the question is: whether the neo-consonantary preceded the neo-syllabary (and its letters were used for -i syllables) or whether the neo-consonantary came later (and the -i signs were chosen for the simple alphabet). The first situation seems to fit the case, as the neo-consonantary is attesested around 1500 BCE, and the neo-syllabary appears around 1200 BCE. Thus the neo-syllabary would have been built around the letters of the neo-consonantary, with new forms and/or stances created for the -a and -u syllables.

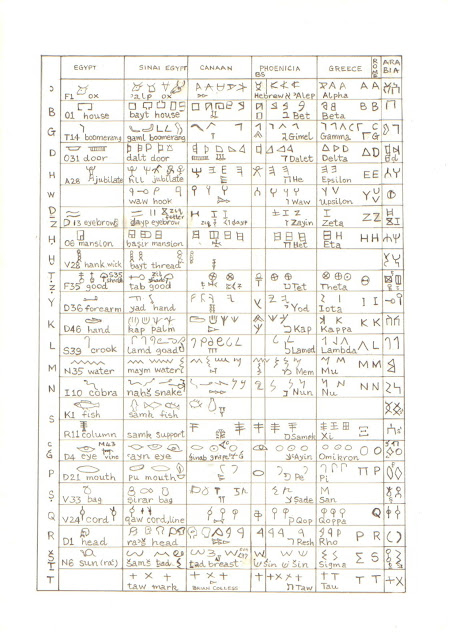

Looking back to the beginnings, the original prototype of the alphabet came out of the West Semitic syllabary in the Bronze Age.[8] At least eighteen of the twenty-two letters (18/22) that survived into the Phoenician and Hebrew consonantal alphabet of the Iron Age were already in that proto-syllabary; this can be seen on the table of alphabet evolution appended below (note the BS [Byblos script] column in the Phoenicia section). For the most part, the syllabograms with –a were chosen for this purpose. The proto-alphabet was patterned after the Egyptian writing system, which did not indicate vowels, but the characters could also function as logograms, ideograms, and rebograms (rebuses).[9] We see this in the proto-alphabetic inscription from Wadi el-Hol in the Egyptian desert, which speaks of feasting in celebration of the goddess ‘Anat, in agreement with the Egyptian inscriptions reporting similar carousing in honour of Hathor.[10]

The new syllabary (the Hebrew neo-syllabary of the Early Iron Age, as distinct from the proto-syllabary of the Early Bronze Age) did not necessarily select the direct descendant of these proto-alphabetic originals for the set 0f syllabograms ending in -a: for example, the Aleph corresponding to the ox-head is not ’a, but little more can be said on this score at present.

Suddenly we realise that we are hearing the vowels as well as the consonants! The writer of the Izbet Sartah says, in my reading of his text (line 1b-2a): “I see that the eye gives the breath of the sign into the ear”. In this statement he uses the ‘Ayin sign for “see” and then for “the eye”, continuing the practice that goes right back to the inception of the proto-alphabet, and also to the West Semitic syllabary that preceded it, whereby the pictophonograms could act not only as consonantograms or syllabograms, but also as logograms, ideograms, and rebograms (rebuses), as happened with the hieroglyphs in the Egyptian writing system, which influenced the formation of these two West Semitic scripts.

Thus, the early Hebrew alphabet of Iron Age I was not the same as the Phoenician alphabet of the Iron Age: it had sixty-six letters (not simply twenty-two), and each of them stood for a particular open syllable (consonant plus vowel, not merely a single consonant), and so there was every indication of the vowels in writing. Moreover, the signs were multifunctional, a concept that is never countenanced in the standard manuals of West Semitic epigraphy.

In summary, here are some indicators for distinguishing the two early Iron Age alphabetic scripts, which we might call (1) the neo-syllabary and (2) the international consonantary.

(1) Various forms for each letter (’abugida syllabary)

(2) Single form for each letter (’bgd consonantary)

(1) Dextrograde, sinistrodextral (L > R)

(2) Sinistrograde, dextrosinistral (L < R)

(1) Fish for Samek

(2) Spinal column (djed) for Samek

(1) Dot in circle of `ayin

(2) No dot in circle of `ayin

(1) Vertical and horizontal forms of Sh-sign (3 and W)

(2) Horizontal Sh only (\/\/)

(1) Logography and Rebography

(2) Consonantal writing only

The broken inscription on the Ophel Pithos from Jerusalem is highly problematic, not having the key indicators (Samek, ‘Ayin, Shin), and with uncertainty about the direction of the writing.[11] It appears to have two forms of Nun (NI and a reversed version) or possibly two different instances of Mem (if the N on the far right is really M); its Het (Khet) is unusual, lacking a central crossbar, and so it seems to be neo-syllabic, possibly H.U (Khu) but not H.I (Khi); the Mem (first letter on the left) seems to fit the MI mould, rather than MU or MA, and so it is not prescriptive either way; the letter following could be R (facing in the wrong direction) or Q (which should have the stem piercing the oval for QI and Phoenician Q), and the next one P (a reversal of the Phoenician P) or L (inverted and reversed). It is thus anomalous as a Phoenician-style text, and this perhaps supports it as neo-syllabic; and so it might have been written before David established his capital there. But it was inscribed before it was baked, and it was not necessarily made in Jerusalem. Incidentally, it is under discussion whether this is a vessel for wine or water or whatever.

Then there is the Qubur el-Walaydah bowl, usually dated early in the Iron Age, and it is quite instructive as far as it goes.

Sh M B? ` L | ’ Y ’ L | M Kh

The bulk of the text is a personal name, the second part (’ Y ’ L) being the patronymic. As stated above, the Sh-sign would be SHU (indistinct on this picture, but it is a "Sigma", not “3” SHA, nor “W” SHI) . The Mem should be MI (though it has more angles than the Phoenician form). Thirdly B or P (but BA seems more likely than PA, because it is the god Ba`al). Then comes ‘Ayin with no dot, so it is ‘I. The Lamed here is not the same as the one further on, and I will not make a decision on their respective sounds; but it might be LI. Hence Shumiba`ili (“name of Ba`al”). Regarding the Mem Khet combination (apparently separated from the rest by another dividing stroke), this could say mah.u “a fatling” (a sacrifice, as at the end of the Wadi el-Hol horizontal inscription, in my reading of it).

Another intriguing inscription comes from Gath, the hometown of Goliath.[12]

The Gath inscription is certainly Philistian, and perhaps its script is a local version of the consonantary or the syllabary. The Qeiyafa Ostracon is from a fort in the vicinity of Gath, but I have reasons for believing its script and language are Israelian. The Zayit alphabet is clearly the international consonantary, and this site is also in Philistia, near Gaza, but it could be Israelian, in the kingdom of David and Solomon. The Qubur Walayda inscription is supposed to be early, and its geographical position (south of Gaza in the Negev) hints that it might be Philistian rather than Israelian; the name Shumi-Ba`ili is not decisive.

Consequently it may well be that the new syllabary was not only used by Israelites but also by Philistines, and possibly Jebusites (in Jerusalem, on the Ophel pithos). In any case, my guess is that the change from local syllabary to international consonantary came about when the Davidic dynasty established cultural and commercial ties with Phoenicia (2 Samuel 5:11-12, 1 Kings 5:1-18, Hiram of Tyre) and adopted the international consonantal alphabet, as used in Tyre, Sidon, and Byblos (the chief supplier of our inscriptional evidence).

And now a question about priority (or priorness): which came first? Was the Phoenician consonantary a reduction of the Israelian neo-syllabary, employing only the -i characters? Or was the Hebrew neo-syllabary an expansion of the Phoenician alphabet, which became the i-column in the new construction?

There are no known alphabetic inscriptions from Phoenicia in the Bronze Age.

[3 September 2016: But see now an inscribed bowl from Byblos:

http://cryptcracker.blogspot.co.nz/2016/08/byblos-bowl-inscription.html]

It is not credible to surmise that the Phoenicians were not writing and recording in that era, but we might assume that they were favouring the original Byblos syllabary, which is attested all around the Mediterranean region and beyond (notably Jamaica[13] and Scandinavia[14]); and their written records would have been on perishable papyrus.

Nevertheless, four Phoenician alphabetic inscriptions (or graffiti) have turned up on clay tablets, in Mesopotamia (from the Sealand, at the Persian Gulf) from the end of the First Dynasty of Babylon, that is, around 1600 BCE. Amazingly the letters have the same forms as the Iron Age consonantary. One of them is a transcription of the name Ali-dîn-ili. For our purposes it is unfortunate to see so many –i syllables in it, but we can say that the same form of Aleph is used in Ali and Ili (an acute angle with a vertical line running through both sides, and pointing leftwards, the expected direction of the writing). Another graffito begins with that form of Aleph, and, judging only from drawings, both texts have the regular forms known from the Iron Age (the Tel Zayit alphabet is invoked by the reporting researcher, for comparison). One exception is Yod, which is uncharacteristically reversed. This surprising evidence needs closer scrutiny and confirmation of its date.[15]

In the nineteenth century the bones of the Ichthyosaurus lay “unpublished” in glass cases in the Ashmolean Museum for a hundred years or more; they were disturbing to the consensus. In our own times, photographs of two ’abagadaries of the proto-alphabet (which were discovered in southern Egypt and included by William Flinders Petrie, in 1912, in the frontispiece of his book The Formation of the Alphabet) have been disregarded and not taken into account in all the published discussions and speculations that have gone on in this realm; and they are not mentioned in any of the handbooks on the subject.[16]

The climate is changing drastically around us, and apparently the paradigm has now shifted in West Semitic epigraphy. Still, this neo-syllabary (which has been posited here) could be a hypothesis that can be easily falsified; but the variation in forms of letters in a single inscription such as the Qeiyafa Ostracon requires an investigation.

I have chosen to announce my findings here, because of the strong connection with ASOR that the forerunners had, namely William Foxwell Albright and Frank Moore Cross, and I regret that they did not live to share in this new knowledge. Unfortunately their successors sometimes fail to test the theories of these masters, upholding the proposed identifications for the signs of the proto-alphabet without taking sufficient account of other possibilities.

I have been inspired by the words of another keen practitioner of this art and science, namely Gordon J. Hamilton, who said (on the internet) that the recent discoveries of such inscriptions should have the effect of “motivating researchers to dig deeper and reconsider previous views”.

We must also try harder to read these important texts. In line 3 of the Qeiyafa Ostracon, I discern this sequence: M T G L Y T B ` L D W D, and the syllables seem to reveal GULIYUTU and DAWIDU, and the meaning is: “Goliath is dead, David has prevailed (ba`ala)”.[17]

SYNOPSIS

proto-consonantary (proto-alphabet, closely related to the syllabary, but 27 consonants; also logographic)

neo-consonantary (22 letters, the basis of all alphabets)

neo-syllabary (the 22 letters have 3 forms and/or stances, as seen on the Izbert Sartah and Qeiyafa ostraca)

(2) Before 3000 BCE in Egypt a complex pictophonographic logoconsonantary was created; its pictorial and symbolic hieroglyphs became stylized and unrecognizable (in the Hieratic script), but the original shapes of its logograms and phonograms (simple and complex consonantograms) were preserved for monumental inscriptions. Generally, vowels were not represented.

(3) Proto-syllabary Before 2300 (in the Early Bronze Age) in Canaan (Syria-Palestine), probably at Gubla (Byblos), a simpler pictophonographic logosyllabary was constructed, largely from Egyptian characters, and using the acrophonic principle (a modification of the rebus principle) to form syllabograms (representing a single consonant with a vowel), which could also function as logograms and rebograms. Twenty-two consonants and three vowels (i a u) were represented.

(4) This became the model for other acrophonic syllabic scripts: Aegean (Cretan and Cyprian, 5 vowels) and Anatolian (Luwian, 3 vowels); also American (notably the Maya acrophonic logosyllabary, with 5 vowels).

(5) Proto-consonantary After 2000 BCE (in the Middle Bronze Age) in Egypt, apparently, the West Semitic proto-alphabet was constructed as a simple logoconsonantary, largely from elements in the West Semitic syllabary and thus based on Egyptian hieroglyphs; its phonograms were acrophonic consonantograms, which could also function as logograms and rebograms. The number of consonants was expanded from 22 to 27 (or possibly more). No vowels were represented.

(6) This proto-alphabet spread to the Levant (in the Hyksos period, 17th century BCE?) and was used alongside the syllabary (in Egypt and Canaan). No vowels were represented. The number of consonants was retained at 27, but this was, sooner or later, reduced to 22 phonemes.

(7) In the Late Bronze Age, apparently at Ugarit, a cuneiform consonantary was devised, with cuneiform characters based on the pictorial forms of the proto-alphabet. There was a long version, with the full complement of consonants, and syllabic signs for ’a ’i ’u; and also a short version used beyond Ugarit.

(8) Neo-syllabary Early in the Iron Age, in Israel (and Philistia?) a syllabic alphabet appears, “the neo-syllabary”, a new development employing the stylized forms of the proto-alphabet, with a reduced number of consonants (22, the same as in the earlier West Semitic logosyllabary), and with three vowels (u a i) represented by changing the shapes and stances of the letters. The practice of logography persisted, and the signs were multifunctional, as in the proto-alphabet.

(9) Neo-consonantary In the Levant, in the Iron Age, a simple consonantary with 22 letters, conventionally known as the Phoenician alphabet, became the international writing system for West Semitic languages (Phoenician, Hebrew, Aramaic, Moabite, and others). In some cases matres lectionis were added, to compensate for the lack of vowel signs.

(10) In the Hellenic regions an alphabet was invented, with the elements of the West Semitic consonantary put to new uses, including the innovation of vowel-letters (“vocalograms”).

http://www.rollstonepigraphy.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/01/Rollston-op-TelZayit.pdf

Fig 8: Tel Zayit abagadary

http://qeiyafa.huji.ac.il/ostracon12_2.asp

http://cryptcracker.blogspot.com/2007/03/oldest-west-semitic-inscriptions-these.html

http://www.foundationstone.org/resources/Ophel-inscription.pdf

http://cryptcracker.blogspot.co.nz/2013/07/jerusalem-jar-inscription.html

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gath_%28city%29

http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ostracon_de_Tel_es-Safi

Maeir, A.M., Wimmer, S.J., Zukerman, A. et Demsky, A. 2008. An Iron Age I/IIA Archaic Alphabetic Inscription from Tell es-Safi/Gath: Paleography, Dating, and Historical-Cultural Significance. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 351 (2008)

http://cryptcracker.blogspot.co.nz/2012/05/phoenician-bronze-cup-in-jamaica-below.html

Laurent COLONNA D’ISTRIA

http://sepoa.fr/wp/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/NABU-2012-3-FINAL.pdf

Dalley S., 2009, Babylonian Tablets from the First Sealand Dynasty in the Schøyen Collection, CUSAS 9

http://cryptcracker.blogspot.co.nz/2007/10/gordon-hamiltons-early-alphabet-thesis.html

https://sites.google.com/site/collesseum/qeiyafa-ostracon-2

not much pork at QW, no pigs at Beth-Shemesh (see below

Simplicity of undecorated pottery a marker of Israelian presence, versus the rest of the population.

relation with the Israelites (without elaborating the reasons for this relation) and/or its functional suitability to the needs of the IronAge peasants, regardless of their ethnicity.The former was viewed as simplistic and was abandoned by many in favor of the latter. Still, this functional explanation fails to account for the synchronic and diachronic dominance of the four-room house as a preferable architectural type in all levels of Iron Age settlement (from cities to hamlets and farmsteads), all over the country (both in high-lands and lowlands),for almost 600years(!).Moreover, the plan served as a template not only for dwellings, but also for public buildings, and even for the late Iron Age Judahite tombs.Thefact that the house disappeared in the sixth centuryBCE seems also to refute any“functional”explanation, as no changes in peasant life and no architectural or agri-culturalinventions took place at the time.We have therefore suggested that an adequate explanation for the unique phenomenon of the four-room house must relate to the ideological/cognitive realm (Bunimovitz and Faust, “Building identity”; Faust, including

EMERGENCE OF ISRAEL AND ETHNOGENESIS

The Historical Context for the Emergence of Israelite Traits: Israel and the PhilistinesSome of the Israelite traits seem like a straightforward way to differentiate this group from t he

Canaanite sites exhibit either a lowlevel of pork consumption,

for example in Qubur el-Walaydah, or an avoidance of pigs, for example in Beth-Shemesh; cf. Faust and Katz.

In most cases (Gath being an exception) this decreases dramatically during Iron Age II (Faust andLev-Tov,including references). Therefore the time in which avoidance of pork could have become a meaningful ethnic trait must have been Iron Age I, and not later. Interestingly, while some question the sensitivity of even this trait for studying ethnic-ity in the Iron Age, it appears that new data further support its signicance.

Detailed data on the percentage of pork in a number of IronI levels at Ekron show that while the Philistines consumed pork from the time of their arrival–no doubt food habits that carried no ethnic meaning at the time of their initial settlement–they gradually increased the percentage of pork in their diet during Iron I: from 14 percent to 26 percent in the

AVRAHAM FAUST

course of some 150 years (see detailed discussion in Faust and Lev-Tov). Later, in IronIIA, the percentage of pork in the Philistine diet shrank dramatically, hence pointing not only to its ethnic sensitivity in theIronI,but also to the fact that IronI was the onlypossible historical context for the emergence of this trait as an Israelite-specic ethnicbehavior. The tradition of not decorating pottery could also reect an attempt to differentiate the Iron Age I highlands settlers from the Philistines, whose pottery was highly decorated. The Philistine decorated pottery of Iron Age I disappears during the transition to Iron Age II; hence, the absence of decorated pottery could have become an ethnic marker only in Iron Age I. Notably, Philistine pottery was clearly ethnically sensitive in Iron I, as can be seen in its very bounded distribution, that is, its complete absence intheEgyptian-Canaanitecentersof thersthalf of thetwelfthcenturyBCE (Bunimovitzand Faust, “Chronological separation”). The fact that this pottery was ethnically sensitive is attested not only by its absence in Egyptian-Canaanite and, later, Israelite settle-ments, but also from sites within Philistia, as the percentage of this decorated pottery grew throughout IronAgeI,before completely disappearing in IronIIA(FaustandLevTov). This is true for other traits aswell,but these examples are enough to show that these behavioral patterns could not have been created after Iron Age I. These factors alone make it highly unlikely that Israelite ethnic identity was created only in IronAgeII, and clearly point to Iron I as the time of Israel’s ethnogenesis. It is worth mentioning briey the issue of circumcision. This trait can hardly be discussed on the basis of archaeological reasoning, but other lines of evidence clearly connect this trait with the Philistines.It is quite clear that the term“uncircumcised”isused in the Bible as an ethnic marker, and since many of the local population of the region practiced circumcision, the trait could have served as a marker only in relation to the Philistines who were foreign and uncircumcised (Bloch-Smith 415). Interestingly, the pejorative term “uncircumcised” is used only in texts that relate to Iron Age I; thus it appears that the Philistines adopted circumcision during Iron Age II as part of their acculturation process (see also Herodotus II:104). In other words, circumcision may have been practiced earlier but have become ethnically signicant only as a result of the interaction with the Philistines, and this could have occurred only during the IronAge I.

The Historical Background for the Israelite-Philistine Interaction

At the end of Iron Age I and during the transition to Iron Age II, that is, the eleventh and beginning of the tenth century BCE, many highland settlements were abandoned.The population became concentrated in fewer settlements that, as a result, becamelarger. All the famous small Iron Age I “settlement sites,” such as Giloh, Khirbet Rad-dana, Ai, Izbet Sartah, Mount Ebal and many others, were abandoned, while sites likeTell en-Nasbeh (Mizpah), Dan, Bethel and others grew signicantly in size, and eventually became towns in Iron Age II. The explanation for this process of abandonment is,rst and foremost, the Philistine military and economic pressure on the highlands, and