THE LACHISH JAR SHERD:

AN EARLY ALPHABETIC INSCRIPTION DISCOVERED IN 2014

Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research,

Obviously Sass is the author of the epigraphical section of the article (p.236-243; his name appears first on the otherwise alphabetical list of four contributors: Garfinkel, Hasel, Klingbell) and I will take this opportunity to respond to his views on the origin and early development of the alphabet, as I have done for Gordon Hamilton and Orly Goldwasser. I give notice that I intend to be critical of his blinkered approach. We both published our own major study of the genesis of the alphabet in 1988, and I have constantly cited him in my subsequent articles. Unlike Hamilton and Goldwasser, Sass has never taken account of my research on this subject. Apparently he is unaware of the new instruments I have offered for classifying West Semitic proto-alphabetic documents and identifying their letters; and he ignores (whether accidentally or deliberately) my idea that the characters of the original alphabet could be used not only as consonantograms but also as logograms and "rebograms" (or "morphograms").

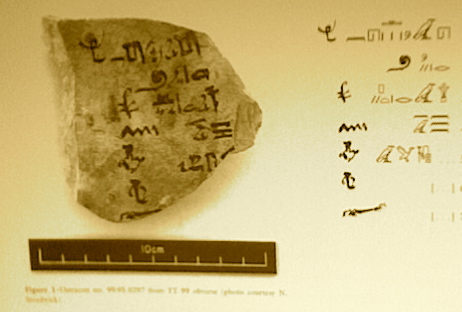

An introductory article on the Lakish sherd appeared in the Times of Israel (10 Dec 2015). Its photograph (click on it to see the whole picture) is large, but the BASOR article (p.235) has two clear photographs and three drawings.

Notice that the letters were inscribed before firing (p.233b) so it is a sherd from an inscribed jar, not an ostracon, like the Izbet Sartah, and Khirbet Qeiyafa ostraca, which are on sherds that are used as tablets (drawings of these and other relevant inscriptions are presented on pages 237-241). It therefore belongs to the same category as the Khirbet Qeiyafa jar.

However, whereas the Qeiyafa jar and the Jerusalem Ophel pithos yielded more than one piece of their pots to the excavators (but not enough to reveal the entire text in each case), the Lakish sherd stands alone, and apparently its text is incomplete. It was found in a temple area, and this might give a clue to understanding its inscription and its connection with the artefact.

Note: I prefer to write Lakish, as the ancient inhabitants would have said it, rather than Lachish or Lakhish.

The two Qeiyafa texts (ostracon and jar) differ in the direction of their writing: the ostracon's lines run from left to right (dextrograde), and the jar's single line goes from right to left (sinistrograde).

Let it be said at the outset that my recent research leads me to the hypothesis that these two ostraca (Izbet Sartah and Qeiyafa) have syllabic writing, that is, each letter has three different stances or forms for distinguishing their accompanying vowels (for example: bi, ba,bu); this may be designated as 'the neo-syllabary', which was constructed from the letters of the early alphabet, and those proto-alphabetic signs were originally borrowed (at least eighteen of them) from the West Semitic 'proto-syllabary' (the Byblos script, which West Semitic epigraphists are reluctant to look into, terrified of having their reputation ruined).

My term for the original alphabet is 'the proto-alphabet', as the prototype of the consonantal script that developed into the Greco-Roman alphabet, but it was used as a syllabary in early Israel (and later in Ethiopia, India, and Southeast Asia, but this statement needs clarification and refinement). Sass (236a, n.3) speaks of 'early alphabetic inscriptions', and he offers 'pre-cursive' as a new technical term to cover the various labels already in use, namely 'Proto-Canaanite', 'early Canaanite', and 'linear alphabetic' (as distinct from 'cuneiform alphabetic'); he makes no reference to my 'proto-alphabetic'; but 'proto-alphabet' is not meant to be a formal word.

For the sake of precision, I would have to say that the original alphabet was a picto-phonetic system which functioned as a logo-morpho-consonantary: the signs were pictorial, acrophonically standing for the first consonant of a West Semitic word that goes with the image, but also allowing the picture to represent the whole word, or all of its sounds for use in forming other words in writing; thus the snake-sign says N from n-kh-sh 'snake', or 'snake' in any language (logogram), or as a rebogram with the addition of -t (NKhSh-T) 'copper'. That is how the Egyptian hieroglyphic script worked, and it should not be hard for us to accept that the first alphabet, although it was a major simplification, could carry those features (remembering that our earliest proto-alphabetic documents come from Egypt and Sinai).

These ideas are not (yet) known in handbooks on the early alphabet, nor in articles such as the one under review here. This view of the history of early West Semitic ('Canaanian') writing systems is not yet acknowledged as 'received knowledge'.

Now, the city of Lakish has bequeathed a valuable collection of inscribed objects from the Bronze Age (dagger, bowl sherd, ostracon, ewer, bowl, censer lid, sherd, bowl fragment, and the late epistolary ostraca from the 6th Century BCE) and we are glad to welcome this new one and any others that the current excavations may bring to light, including the missing parts of this one (233b). All these brief but valuable documents show various stages of the development of the alphabet, from pictorial (the dagger) to cursive (the Lakish letters).

For information on the Bronze Age items from Lakish, see:

Benjamin Sass, The Genesis of the Alphabet, 1988, 53-54, 60-64, 96-100;

Emile Puech, The Canaanite inscriptions of Lachish and their religious background, Tel Aviv 13-14, 1987, 13-25;

Brian E. Colless, The proto-alphabetic inscriptions of Canaan, Abr-Nahrain (Ancient Near Eastern Studies) 29, 1991 (18-66), 35-42.

The three lines on the new Lakish sherd can be transcribed thus (reading from right to left):

L K P [

R P S [

` P/G [P?] [

As a general rule it can be stated that Iron-Age neo-syllabic texts run rightwards, and consonantal alphabetic texts run leftwards. It seems clear enough that the direction here is sinistrograde (right to left) and thus the script should be consonantal rather than syllabic (according to the hypothetical principle stated above, which is based on the available evidence). But the question remains whether this practice was only Israelian, and not Canaanian, or Philistian. From their context and content, I read the two ostraca (Figs. 14 and 19) as Israelian; the Gath Sherd (Fig.15) would presumably be Philistian.

A tentative reading of the text as it stands might be:

Pikol the scribe (spr) .....

Pikol is found in the Bible (Genesis 21:22) as the name of the commander of the Philistine army of Abimelek of Gerar.

For the scribe (spr) there are numerous examples in the Hebrew Scriptures, but 'Ezra the scribe', alias 'Ezra the priest' (Nehemiah 8:1-2) is an interesting case, if the square sign below the p and r is an archaic Bet, and like the square on the Gezer sherd (from a cult stand) it could be a logogram for 'house' or 'temple', then Pikol could be a scribe of the sanctuary in which the object was found. Incidentally, Fig.8 (Gezer sherd) possibly has the drawing in the wrong stance: the hand should not be pointing upwards but to the right, the snake should probably be horizontal, and the house should have its opening at the bottom, as in the instances on Figs 4 and 5 (from Lakish) though both are different from each other and from the Gezer Bet; however, as it stands, it has a parallel in the drawing of Sinai 352 (Fig.10); note that most of the Sinai instances of Bet have no gaps in the four sides.

The point is that the Gezer sherd says kn B, 'temple stand', and here we might have spr B, 'temple scribe'.

Nevertheless, the supposed B here could be `Ayin, an eye, though we are told the apparent dot in it is illusory and therefore not included in the drawings. The third line might have been pg` (root meaning: 'meet' or 'strike') 'stricken' (with some infirmity?). A name Pag`i'el existed (prince of tribe of Asher, Numbers 1:13).

The text is finally regarded by the authors as "undecipherable" (236a), since, for example, pr could be 'fruit' or 'bull'. Indeed, we can play many games with it: 'the mouth (p) of every (kl) scribe (spr)'.

One possibility needs to be examined: 'flask (pk) for (l, belonging to) the scribe (spr)' (unless it is 'fruit-juice flask', allowing the Samek to be Cretan NE, which derives from nektar, in my view; see below). We must always remember my guiding principle: only the writer of a text knew what it means! And since the words were added before the pot went into the oven, they would presumably state the purpose of the vessel, or identify the owner, or both.

The word pak denoted a flask or cruse, such as 'the cruse of oil' that Samuel emptied on the head of Saul on the occasion of his anointing as king (1 Sam 10:1). It is usually assumed that this vessel was small, but the reconstructed jar (Fig,2 f) is about 35 cm tall, though this is not certain, as they admit (236).

So, it is worth proposing this interpretation:

Flask for the scribe [P]G` |

For the remainder of the article(236-244) "palaeography is the principal subject".

The Samek in the middle line comes as a pleasant surprise: it is hailed as "the earliest secure occurrence of the letter" (p.242a). What we should say, however, is that here we see another example of that particular form of Samek which depicts a spinal column (root smk 'support', denoting stability, as in the corresponding Egyptian hieroglyph R11), as distinct from the other form, a fish (samk); in my opinion (not widely accepted) there are actually two allographs (alternatives) for Samek. Here Sass refers us to his 1988 discussion (p.126 on original Samek, and also p.113-115 on Dalet) where he reports that the fish had formerly been acknowledged as S, but Albright argued in favour of the value D (as in dag 'fish'), and, let me say, most have unfortunately followed this false lead. When they look at the alphabet on the Izbet Sartah ostracon (its bottom line) at the point where Samek should be they see neither the fish nor the spine, and they are puzzled at this 'nondescript' and 'unhelpful' character (Sass et al 2015, 244a); but it is a fish (as Emile Puech will also testify).

The letter Dalet is a door; its name means 'door', and "D is for door" has always been the case, though originally it was "Dalt is for D", with the picture of a door representing the sound d, by the principle of acrophony. The trouble is that the door-signs, even though their door posts are clearly shown, have been regarded as fences (or sometimes even accepted as doors) and interpreted as Het (H.) (Sass 1988, 117-120). Thereafter the dominoes keep on falling and the truth about several other letters disappears. Gordon Hamilton (under the guidance of Frank Moore Cross) tries to have the fish and the door as allographs of D, but this argument is not helped by the occurrence of a fish and a door side by side on a Sinai inscription that Sass displays for us (Fig. 11, Sinai 376).

Gordon J. Hamilton, The Origin of the West Semitic Alphabet in Egyptian Scripts, 2006, 61-75

The fish and the spine both occur on a tablet which shows the letters of the proto-alphabet, from Thebes; however, this is not a text but an abgadary: the spine and the door are together at the top, and the fish is below the spine (see section 17 S here); in the cuneiform alphabet from Ugarit, there is a counterpart to the djed column, with three crossbars, standing for `S (as noted by Sass, 242a); a representation of a fish (apparently) was employed for cuneiform Samek as S; the cuneiform Dalet is unmistakably a door. See my study on the cuneiform alphabet as an adapted version of the pictorial proto-alphabet.

Focusing again on the Samek on the sherd, it has to be said that there is a counterpart on the Lakish dagger, though it lacks the bottom horizontal line, and it resembles a telegraph pole with only two cross bars.My reading of its four letters (bag, head, snake, spine) is S.R N S, which can say "Foe flee". By contrast, Hamilton (390-391) makes the Samek a double cross for an anomalous T, turns the tie of the bag into Dh, and the body of the bag into L, producing Dh L RNT, "this belongs to Rnt", a name that would correspond to Biblical Rinnah (1 Chron 4:20), which is a man's name , though it looks feminine ('Joy'); but this is an unnecessary hypothesis, based on a stubborn refusal to recognize the tied bag as the letter Sadey (S.).

Hamilton (2006, 197, n.254, uses the term 'bizarre' to describe my acceptance of this character as a bag and as Sadey; he wants it to be a monkey (qop), and he mistakenly identifies it as Qop, thereby rejecting the sane suggestion of Romain Butin (to whom the book is dedicated in memoriam) that it was Sadey, though Butin was not sure what the sign depicted.

Sass has conveniently provided (Fig. 9, Sinai 349) Albright's drawing of an inscription which contains the word that has caused all this confusion. The second line has this sequence: head, house, snake, bag, house, snake, that is, rb ns.bn, which means 'chief of the prefects', and he would be the supreme leader of the Egyptian turquoise-mining expedition. The erroneous view (with the bag as Q rather than S.adey) produces 'chief of the borers' (understood as 'miners'); but the miners were not the only members of the work force; the metalworkers were the essential part of the team, because they made and repaired the copper tools, and they were Semites (as we know from the Egyptian inscriptions on the mining site).This stela (Sinai 349) refers to their equipment ('nt in the top line, and `rk in the third line).

On the stela reproduced below it (Fig. 10, Sinai 352) they describe themselves as bn kr ('sons of the furnace') and the letters accompanying the large fish (which is S not D) specify that they are 'pourers of copper' (nsk N) , with one of the snakes acting as a rebogram for NKhSh, not 'snake' but 'copper'(which does not always need a final -t). The two letters at the top of this column (an ox-head for Aleph and a sun-symbol for Sh, from shimsh, 'sun') say 'sh, 'fire', and this stela marks the spot where their fire burned. These examples show the true origin of Sadey as a bag, and Samek as a fish, but the fish did not survive into the Phoenician and Hebrew alphabet of Iron Age II.

The simplified form of of the spinal Samek, with only two crossbars on a vertical stem, was already present in the proto-syllabary (the Byblos script), representing the syllable SI, together with a 'monumental' character that matched more closely the original hieroglyph (R11), and this should not be dismissed as inadmissible evidence, since there was a close relationship between that syllabary and the consonantary (the proto-alphabet) that it engendered. I presume that it likewise stood for si in the new syllabary, though it is not yet attested. However, the legible and identifiable signs in this text (P, K, L) correspond to PI, KI, LI, though the presumed R has its head facing in the wrong direction

But there is cause for concern in the shape of the character on the Lakish sherd: comparing the drawing and the photograph (p.242a) we observe that the middle line is not perfectly straight but curls round on the right side. A counterpart can be found in the Linear A syllabary of Bronze Age Crete, in some forms of the syllabogram NE.

My work in progress on the syllabary of Crete (and Greece and Cyprus) is summarized here: The Cretan scripts. I espouse the minority view (first proposed by Cyrus Gordon) that at least some of the Linear A inscriptions in Crete were West Semitic. I see the NE sign (acrophonically derived from nektar, the divine drink) as a libation vessel with a handle and a spout, and it has no connection with Egyptian hieroglyph R11 (the djed, a straight spine, a symbol of stability).

Here I must record that the writing of this essay was neglected while I looked again at the Linear A inscriptions on Cretan offering altars, and I realized that they are in Canaanian (Phoenician/Hebrew) saying:

"I bring my offering of new wine/beer/olives/blood, O [name of a deity])". These rites were performed at 'peak sanctuaries', equivalent to the 'high places' condemned by the prophets of Israel. Remember you heard it here .The work in progress is viewable at CRETO-SEMITICA and CRETAN SEMITIC TEXTS.

In this connection, a Cretan syllabic inscription has been discovered at Lakish, and it is likewise dated to the 12th C. BCE (both from Level VI, apparently). It is described as a Linear A text, though this was the age of Linear B, a Hellenic script derived from Linear A, which itself was a reworking of an older set of pictorial characters; the RI sign (originally representing a human leg) is more like a Linear B form, though reversed. The sign for NE does not appear in its brief text.Note that it was a piece of a large limestone vessel which seems to have been made locally.(A thought: Linear A continued to be used for Semitic writing outside of Crete.)

On the potential significance of the Linear A inscriptions recently excavated in Israel. Gary A. Rendsburg, Aula Orientalis, 16, 1998, 289-291

The sherd we are studying here is dated to the 12th Century BCE, but it has the letter forms of the Phoenician alphabet. And now we have two astonishing signature inscriptions from the Sealand (southern Mesopotamia), dated to the end of the 16th Century BCE (Late Bronze Age). Their direction of writing is sinistrograde, as with the Phoenician alphabetic inscriptions from Iron Age II, and the letter forms are much the same as those in the Phoenician alphabet of the Iron Age (NABU 2012 no.3, 61-63; there is no Samek for comparison, though L,P, G, `Ayin, and other letters are attested; but not much can be said; these match their later counterparts, but for the Lakish sherd the Qeiyafa and izbet Sartah ostraca offer more examples. In this respect, Joseph Naveh (1978, 35) is quoted (237b, n.11) to warn us about the Izbet Sartah writer's "confusion of letters and his mistakes" which would be due to his "poor training or bad memory". Certainly we can see from his first words in line 1 that he is a beginner: "I am learning the letters" ('lmd 'tt), but it seems that his variations for each letter (as compared with the models he presents in line 5) were intentional, and what he was learning was the new syllabic use of the alphabet as practised in early Israel.

Here is an opportunity to look at my neo-syllabary hypothesis, using the drawings available in this BASOR article: Izbet Sartah ostracon (Fig.19), Qeiyafa ostracon (Fig.14, Ada Yardeni), Qubur el-Walayda bowl (Fig.6); and pictures of them here).

All three are dextrograde, and exhibit variant forms for their letters. From my observation, as a rough rule, the Izbet Sartah alphabet shows the -a syllabograms; the Phoenician alphabet has the forms that were used for -i syllable-signs; the -u signs are the left-overs.

Consider the case of the letter Shin. The first sign on the QW bowl is clearly a form of Shin (originating from a depiction of a human breast, thad/shad, according to my system): the breasts are pointing to the left.The Izbet Sartah Shin has the breasts on the right (sha?). At the beginning of the second line of the Qeiyafa ostracon, there is an equivalent sign in a word that can be read as sha-pa-t.a ('he judged'); and at the end shi-pi-t.i ('judgements'), where the breast is horizontal, as in the Phoenician alphabet; the QW bowl has a personal name, Sh-m-b-`-l ('Name of Ba`al'?), and shum is the expected ancient form (Hebrew shem). So we seem to have successfully identified the three syllabic forms of Sh (sha, shi, shu). Notice there is no dot in the QW eye-sign (a circle, incomplete) as in the Phoenician alphabet, so this should say `i. The preceding letter would presumably be ba, though it differs from the IS B-sign; nevertheless, in line 3 of the Q ostracon we have the sequence ba`ala, where the `Ayin has a dot (as on the IS alphabet), but here we see another verb ('he has prevailed') not the name or title Ba`al, in my view.

For the record, here is my tentative reading of the Qubur el-Walayda bowl inscription ("12th-century context")

shu mi ba `i li | 'i ya 'i lu | ma h.u

Ugaritic name ShMB`L (cp. shum-addi)

The second name is the patronymic, presumably ('son of I').

The last word means 'fatling' (mah.u) and possibly refers to a sacrificial offering.

This exercise will not be consummated here, but note in passing the two opposing p-forms in the 'judge' words in the Qeiyafa ostracon, line 2: one is pa (the IS form) and the other is pi (with the stance of the P on the Lakish sherd and in the Phoenician alphabet).

Reverting to Sass's treatment of the Lakish sherd inscription, and the comparative material he employs, Sass dismisses some known inscriptions as pseudo or irrelevant, and others he tacitly ignores. possibly because they were discovered by unsuitable anonymous people (such as the two unprovenanced copies of the proto-alphabet which Flinders Petrie obtained in Egypt; at the start of the twentieth century; these could not have been forgeries, as even the Phoenician alphabet was not well understood). One could suggest ignorance and arrogance on the part of some academics who set themselves up as experts in this field of research; it is not a case of scientific scepticism and rational caution, but wilful obfuscation and reprehensible avoidance of some parts of the available evidence. There is needless agnosticism ("samek is still not identified with certainty in the Proto-Sinaitic inscriptions", speaking for himself). There is doctrinaire dogmatism in dating the Wadi el-Hol and Sinai inscriptions to the 13th Century BCE (237a, n.8), leaving little time for development of the letters from pictorial to stylized forms. This is his ultra-low chronology, putting ages in chaos; originally he had presented the case for Middle Kingdom versus New Kingdom, and now his compromise is to put them at this impossibly late stage. The proper solution is to recognize that some are MK and others are NK.

Even if Sass rejects my ideas, he must take account of the numerous inscriptions I have brought into the picture.