This is the second part of a a series on

West Semitic Syllabic and Consonantal Scripts

https://cryptcracker.blogspot.com/2021/12/lakish-inscriptions.html

http://cryptcracker.blogspot.com/2021/12/lakish-scripts.html

https://cryptcracker.blogspot.com/2021/09/khirbet-ar-rai-inscription-lyrbl.html

https://cryptcracker.blogspot.com/2022/11/lakish-lice-comb.html

from Tel Lachish

Our new Lakish inscription

may not have enough graphemes for us to classify it definitively, but

the ruin-mound of the city has provided several examples of the script

categories, which may assist us in our quest.

(1) The proto-syllabary

Here are two more inscriptions on sherds from Lakish (written in ink); they were published in the journal Tel Aviv

3 (1976) 107-108, 109-110, and Plate 5. Both objects were found in

Palace A in 1973. They each include letters that are known to me as

exclusively proto-syllabic, together with signs that could be syllabic

or consonantal. Many years ago my son Michael in Sydney made me a

photocopy of these articles, thinking they might be useful to me, and

they have languished ever since in an unstudied state, but have now miraculously and serendipitously revealed themselves at exactly the right time.

[13] A proto-syllabic inscription from Lakish

the pentagonal sherd

The inscription on the pentagonal bowl-fragment was studied by Mordechai Gilula, who thought it was "Egyptian hieratic", comparable to examples from the 19th and 20th Dynasties, and in line with Ramesside inscriptions found in Lakish.

(https://cryptcracker.blogspot.com/2007/07/alphabetic-sphinx-of-sinai-this.html)

RU BU LA BI NA YA PA BA GA NNA TU HU

Abundance (rubu) for (la) my son (binaya) and (pa) in (ba) his garden (gannatuhu)

This reading, although tentative, provides a clue for the interpretation of the triangular sherd. Possibly some of the signs have been misinterpreted in this interpretation, but the important part is gannat, "garden"; I think this word also appears on the new Lakish rectangular sherd (notice GNNT in the lower part of the text, on the photograph at the top of this page).

This reminds me of the little pieces of paper with prayers in Hebrew placed in the interstices of the Western Wall at the site of the Jerusalem temple; sherds were the equivalent of scrap paper in the olden days.

Returning now to the triangular sherd, our task is made difficult by its murkiness. Another impediment is that there may be some syllabograms that were not attested in the Byblos texts, on which the Mendenhall-Colless decipherment is based; we certainly need to find such signs, but it is hard to discern even the characters we already know in this time-ravaged document.

Does the second line suit the oracular genre? LA (night) DA (door) RA (head) YA: "to/for my circle, family, generation, dwelling"; but if the dot in the head is for doubling (rather than depicting an eye) , then this could say "for liberation" (Hebrew dror) with regard to slaves and captives. Another BI follows the YA, perhaps, and then the 'U (ear); this sequence produces a possible verb, yabi'u, "brings" (root BW' "come"); the ink blob at the end of the line looks like a fish, which should not trespass into the proto-syllabary, but if we allow it, the preceding sign is a circle, SHI (sun) and with the SA (fish) the root ShSS (plunder) emrges.

Can the top line reveal a theme we can grasp? The first letter is the familiar BI, (eye with three tears); next perhaps a dotted circle, SHI (sun), but it is more like a quadrilateral diamond figure, and thus H.U (h.udshu, new moon, or month), and this suggests that a date is being given; then we are confronted by a small square (BA, house?), but it has an upper part, making it as tall as the BI, and a door with two panels, denoting DA. At the midpoint of the line we have a mess of smudged letters requiring long consideration .... Desperation is creeping in.

On the other hand, if the combination is simply BI-NA-T-, "daughter", parallel to the "son" (bin) on the other ostracon, then the mysterious garden and the mystical prophet disappear. However, the possibility still remains that it is a prayer.

The Lakish Dagger

Could it be proto-syllabic? R could be RA, and S could be SA; but the syllabic snake for NA is invariably the cobra, not the horned viper; and Sadey is not attested in the proto-syllabic texts at our disposal. On the other hand, the fish is the normal Samek in the Sinai proto-consonantal inscriptions, and the Samek with two crossbars is the prevalent form in the Byblos proto-syllabic texts; only the two monumental inscriptions (A, G) have the three-bar Samek, in a form that shows its origin in the Egyptian Djed hieroglyph (R11, spinal column); the three-stroke Samek first emerges on the Lakish jar sherd (2014), and it is unique in having no protrusion of its stem at either the bottom or the top (see Photo 18 below, with discussion); again it is uncertain whether this jar inscription is consonantal (neo-consonantary) or syllabic (neo-syllabary), and whether its Samek is simply S or SI; for the neo-syllabary, SA has been identified as a vertical fish with head downwards (Izbet Sartah ostracon), SU is the fish with head upwards (Qeiyafa ostracon, line 4), and we might expect a horizontal fish for SI, but since the characters in the standardised Phoenician alphabet usually correspond to their neo-syllabic -i counterpart, we might presume that --|-|-| (but vertical) would be SI; of course, if this Lakish jar had a neo-syllabic text, then we have found the missing SI, but this argument is going round in circles and that is a prohibited practice.

Nevertheless, in seeking to solve this mystery of the non-identical Samek twins, we can point to places where they were together.

Returning to the Lakish dagger, if it is in fact proto-syllabic (s.ar nas, Foe flee) then we have found the syllable S.A (tied bag) to add to the table of signs, which has nothing to show for that consonant. However, that lifelike human head is troublesome, since only stylized forms of heads are found in the Byblos proto-syllabic texts. Short inscriptions such as this, and the new Lakish sherd, always make our heads spin as we endeavour to categorize them, and to extract their meaning.

Lakish ostracon (or Bowl 2, Sass Fig. 258; Colless, Fig. 06, 38-39)

sh y ` d r l l l

An offering of the flock to Lel (goddess of night)

(Did the bowl contain blood from the sacrificed animal?)

Lakish ewer (Sass Fig. 156-160; Colless Fig. 07, 39)

m t n : sh y [l r b] t y ' l t

A gift (or Mattan) : an offering to my lady Elat

Are they syllabic? No, since they both have the Lamed that does not have a place in the proto-syllabary; likewise the Yod. So the next question will be: Is this the longer or shorter consonantary? If we focus on the word for offering, it is thought to have Th not Sh originally, though Richard Steiner disputes this; the problem is that in the neo-consonantary the Thad (breast) consonantogram has replaced the Shimsh (sun) sign, to represent both Th and Sh, and they look very much alike (if the solar disc is not included with the serpents); but in one instance the breast is depicted vertically (Wadi el-Hol), and in Sinai inscription 375 it is inverted in the word ThLThT, "three" (cp. ShLShT on a Lakish bowl, 08); the four Lakish inscriptions in Fig. 17 are apparently all using the short alphabet, and two have vertical Sh/Th, and two have a horizontal version. There is much debate over the point in time when these two sounds coalesced, and the change from long to short alphabet is brought into the discussion, and fourteenth century BCE (for example) is proposed; but we need to remember that in the proto-syllabary (Early Bronze Age!) Sh and Th were not differentiated, so the breast said SHA and the sun was SHI; but more work needs to be done on the sibilants that were represented by Sh and S signs in the proto-syllabic texts (and we require many more documents to aid us in this research).

Lakish bowl (Fig. 08 above), found in a tomb:

b sh l sh t | y m | y r h.

On the third day of the month

The reading of the first of the three sections (notice the two dividing strokes) is clear: it is the number 3 (written as a word), originally th l th t, but now sh l sh t, though it is the original Th sign representing it here, and so the evidence for long or short alphabet is ambiguous; but in this case the word yrh. (moon, month) assists us; its final consonant was etymologically H, but here it is H.; this indicates the shorter consonantary.

A more recent sherd arrived in 2014, again from a temple: its inscription had been engraved into the jar before firing;

https://cryptcracker.blogspot.com/2019/12/lakish-jar-inscription-new.html

This inscription is not proto-syllabic, though it might be neo-syllabic, but is probably neo-consonantal. It will be examined in the next section.

https://cryptcracker.blogspot.com/2014/04/early-hebrew-syllabary.html

Beth-Shemesh has an interesting and amusing sherd with a local version of this system.

https://sites.google.com/site/collesseum/winewhine

Note that I am constructing a table of signs (not ready for publication yet) with three columns, one for each of the three vowels (u a i), and to the right of the -i column another three columns of later examples of the consonantal alphabet, showing that the -i syllabograms were usually the same as their consonantal counterparts (for example, DI = D, triangular like Delta). I was able to complete the Shu Sha Shi row with additional assistance from the Qubur Walayda bowl; that town is thought to have been a Philistian settlement, and the fact that the inscription has Baal and El names may indicate that the Philistian immigrants were Semitic, but other explanations are conceivable.

If it is interpreted as neo-syllabic, the text could be read thus:

"Jar (pik) for (li) measuring (sipir) 5 hekat (of grain)"

The first question we must ask about the new Lakish inscription is this: Is its script the proto-syllabary, or the proto-consonantary, or the neo-consonantary, or the neo-syllabary? It is obviously not the cuneo-consonantary, the cuneiform alphabet, since there are no wedge-shaped (cuneiform) components in its characters (see Photo 5 above).

Nobody else thinks this way when confronting a new inscription,

applying this four-pronged research instrument (well, I know one person

in Israel. whose name is Geula, and she has inspired me to see the

proto-syllabary in this particular case); but this is the right way to

go.

Ask the question! Is this inscription syllabic (proto-syllabary or neo-syllabary) or consonantal

(proto-consonantary or neo-consonantary)? In this instance, my

preferred response is to say: It is always difficult to decide, because

the proto-syllabary and the proto-consonantary share so many signs

(since most of the consonantograms are converted syllabograms); but the

neo-syllabary can probably be excluded, as it was a phenomenon of the

early Iron Age, and this (allegedly) securely dated missing link is from

the Late Bronze Age; also the readily recognizable D (a rectangular

door) is not one that matches any of the three D-syllabograms (DU and DA

are rounded, like Roman D; and DI is triangular like Phoenician Dalet

and Grecian Delta).

A significant archaeological detail needs to

be inserted here: Lakish was destroyed by fire (by Egyptians, or

Israelians, or Philistians?) and was unoccupied in the Iron Age I (12th

and 11th centuries BCE). In the history of Israel, that is the period

of the Judges and the reign of King Saul; by my calculations, that was

also the time of the neo-syllabary. Therefore this new Lakish sherd

(15th century), and the later Lakish jar sherd would not fit the

category "neo-syllabic".

The first step is an examination of the interpretation given by the

editors of the text; they accomplish this in a single paragraph, and my

suspicions are immediately aroused. They have not established the

writer's intention, and they can not make sense of this collection of

meandering characters. Their sources for identifying letters and their

Egyptian prototypes are

Sass, Hamilton, Goldwasser, all unreliable guides in this matter, I

have

to say. They discern two lines of writing, each consisting of three

letters; my first choice would be to say two groups of writing, an upper

and a lower, but they note the presence of two more characters to the

right of the top line, and another between the two lines; my second

choice would be to envisage a single line of text circling from the top

right corner to the bottom right, and possibly continuing upwards to

complete a circle of letters, perhaps along a piece of the right-hand

side that has been broken off, though not necessarily, as there seems to

be a faded letter (a serpent?) filling the gap. Looking ahead to my

ultimate decision, my third approach will be to accept two clusters of

letters, separated by a dot

(or preceded by a dot in each case),

and read them as two words that make a statement.

Here we shall consider the editors' identifications of the signs: the

letter in the bottom right corner is seen as a snake, hence N, and it

corresponds to the Nun of the Phoenician alphabet, albeit in an

anomalous reversed stance, though this form is more consistent with

Greco-Roman N; they identify three more snakes in the marks between the

upper and lower lines of script; if this is correct, then we are

confronted with three different versions of Nun (snakes in various

poses), and so the script being employed in this document could be the

neo-syllabary, since that is how it works, generally speaking; however,

none of the snake stances visible here (including the faded one that I

have mentioned) matches the N-syllabograms in the later neo-syllabic

texts.

However, it seems to me at this juncture that there

are only two N-serpents, both cobras in a different stance, in the bottom line.

Consider now the door-sign, top left; it is readily recognizable as the

original Dalet ('door') and is accepted unquestionably by Misgav and

his colleagues; but if their reference to Hamilton's pages on this

subject are consulted, we are told that Albright had promoted the

fish-sign as D (dag), though Cross and Hamilton accept both door

and fish as alternatives (allographs) for D; actually others and myself

see the fish (Semitic samk, which is frequent in the Sinai

inscriptions, and in the Samek position on the Izbet Sartah abagadary)

as an allograph of Samek (the spinal column, as on the Lakish dagger),

though I wonder whether they represent exactly the same sound (s versus

tsh?); incidentally, if a fish appears in an inscription it is a

consonantal or neo-syllaic text, since the fish did not swim in the

proto-syllabic pool.

Below the door is their elongated snake; I suggest this is a throwstick, G (gamlu),

and that the dot, which makes it look like a snake with a head, is not

part of the letter; it might be a doubling dot, or an unintentional

blot, or an indicator of a new word (corresponding

to the dot in the top right corner).

Beside the door, is

a rectangle, open at the bottom right corner; this is unusual, having a

rectangle with an open doorway for B (bayt, house), but it has a square-shaped analogy on the Gezer sherd (hand snake house, kn B,

'temple cult-stand', where the house-sign is a logogram for '[sacred]

house', and the sherd is from such a 'cult-stand', for incense or

offerings); the object was found at the Gezer high place.

https://sites.google.com/site/collesseum/gezer

Their three choices for their bottom line, naming the letters from

right to left, are NPT, which could be a word for 'honey', as they point

out; this idea certainly appeals to me, in this connection:

https://cryptcracker.blogspot.com/2020/10/ancient-rehob-and-its-apiary.html

However,

we must be suspicious about the first letter being N, and their

identification of the second glyph as P is a desperate measure, and

their quest for an Egyptian hieroglyphic prototype (corner, or a

building tool) is fruitless; they do not even mention 'mouth', which is

the real origin of the letter pe (see the PU on the Lahun heddle jack, above; and this character would be a very twisted remnant of a human mouth, with the bottom lip curling the wrong way.

Finally, an obvious T (Taw); but it seems to have a long stem, and this

suggests it is syllabic; we will now follow this clue.

My tentative tally is eight letters, and none of them appears more than

once, it seems; this is more likely to occur if the script is a

syllabary, which would have three times the number of characters as a

consonantary. I am reminded of the daily puzzle in the local newspaper,

in which nine letters are offered in a grid, and the task is to create

as many words as possible; we could take that approach here and see if

some of the words we find can be brought together as a coherent

statement; but we still have the problem of identifying all the letters

correctly, and deciding whether they are syllabic or consonantal. We

have to consider the possibility that the scribe is deliberately teasing

the readers, by using signs that could be syllabic and alphabetic, and

challenging us to decide which are intended.

We begin again at the

top right corner: the pair of snakes could just as well be seen as two

horns on a bovine head, which could actually be complete as it stands,

without invoking a missing piece of the sherd; it would represent 'Alep

(the 'glottal stop' consonant); the peculiar horns do have analogies, on Sinai 376, and the Lakish lice comb; we also have Bet (Beta), Gimel

(Gamma), Dalet (Delta); this is starting to look like an abgadary, and

we are thinking that a big part of this ostracon, displaying the rest of

the alphabet, has been lost; but these same letters denote 'A, BA, GA,

DA in the proto-syllabary; and likewise the Taw (a cross), but at

present I am agonizing over its syllabic identity, whether TA or TU. If

this assemblage of letters is merely an exercise, perhaps the scribe is

practising the -a syllabograms; this idea would be supported by

the editors' accepting the circular sign (top, centre) as an eye, hence

`Ayin, representing alphabetic `(ayin), but also possibly syllabic

`A(yin). However, the circle stands for the sun in the proto-syllabary,

and represnts the syllable SHI (from shimshu) rather than SHA (from shad

'breast'); to make the sign clearer one or two serpents can be added to

the sun, as seen on the Thebes proto-syllabic inscription (depicted

several times above, Photo 10); the Sinai proto-consonantal

inscriptions invariably have the serpents but not the sun-disc for Sh;

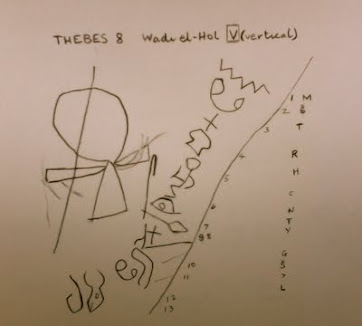

but twice on the vertical section of the Wadi el-Hol proto-consonantal

inscription, we find the sun with a single serpent:

http://cryptcracker.blogspot.com/2009/12/wadi-el-hol-proto-alphabetic.html

While we have this very old inscription in our sights, we may note that

it concerns a celebration for the goddess `Anat, whose name appears

next to her image. We should also ask (as is now our habitual practice)

whether it is proto-consonantal or proto-syllabic. Running down the

sequence of signs, I am surprised to see that each character could be

consonantal or syllabic: water (M or MU), sun (Sh SHI), cross (T T-),

head (R RA), jubilation (H HI), eye (` `A), snake (N NA), boomerang (G

GA), ox-head ('A), and the last letter is obviously L, but this does

not have a place in the syllabary. We have met LA (night) frequently,

and LU (white of eye) on the heddle jack, and LI is a head-rest; so this

text is not syllabic.

The accompanying horizontal inscription

describes the menu for the feast, including wine and sacrificial meat.

The inscription runs from right to left (sinistrograde), beginning with

RB WN, "plenty of wine".

The hank of thread for H is a clear indication that this text is proto-consonantal, since this character does not appear in the prior proto-syllabary or the subsequent neo-consonantary and its offshoot the neo-syllabary;

of course, it has a place in the cuneiform consonantary, which was

modeled on the linear proto-consonantary (see the character of three

vertical wedges on Figure 5 above). Even though the M and N are vertical

on the horizontal line, and horizontal on the vertical line, the bovine

head with the unique feature of a mouth would show the common

authorship and unity of the two inscriptions; it is noticeable that

neither example has a head-line between the horns, as also on our Lakish

sherd, but this particular ox (viewable on the photo below) has an unusual angle for his horns, raising doubts

that the letter is 'Alep/Alpha or syllabic 'A, and that the line on the

left at least is a snake after all (or a Lamed, as suggested by Petrovich 2022); but the analogy of the ox from the

Egyptian desert tempts me to hold on to the Lakish bull by its misshapen

horns. An additional feature pointing to the proto-consonantary is the

vertical breast (No. 10, Th from thad "breast"), with Sh (sun-disc and single serpent, No. 2 and 11) on the vertical line of writing.

The hank of thread for H is a clear indication that this text is proto-consonantal, since this character does not appear in the prior proto-syllabary or the subsequent neo-consonantary and its offshoot the neo-syllabary;

of course, it has a place in the cuneiform consonantary, which was

modeled on the linear proto-consonantary (see the character of three

vertical wedges on Figure 5 above). Even though the M and N are vertical

on the horizontal line, and horizontal on the vertical line, the bovine

head with the unique feature of a mouth would show the common

authorship and unity of the two inscriptions; it is noticeable that

neither example has a head-line between the horns, as also on our Lakish

sherd, but this particular ox (viewable on the photo below) has an unusual angle for his horns, raising doubts

that the letter is 'Alep/Alpha or syllabic 'A, and that the line on the

left at least is a snake after all (or a Lamed, as suggested by Petrovich 2022); but the analogy of the ox from the

Egyptian desert tempts me to hold on to the Lakish bull by its misshapen

horns. An additional feature pointing to the proto-consonantary is the

vertical breast (No. 10, Th from thad "breast"), with Sh (sun-disc and single serpent, No. 2 and 11) on the vertical line of writing.

Contemplate that sun-sign, and then look closely at the circle on the Lakish sherd.

I

have been wondering whether there is a faded line running from the

bottom of the circle, making this letter equal in size with the B and D;

if indeed there is (Eureka!) then the character says Sh or SHI, and not

` or `A.

The resultant Sh B sequence raises the possibility of

"return" (originally ThWB) or "take captive" (ShBY). Here is a possible

combination, involving seven of the letters:

'A SHI BA DA GA TA

"I catch fish"

This would be a sign upon his door, saying ""I am catching fish", equivalent to "Gone fishing, instead of just a-wishing".

Stop the press: there is a problem with the supposed sun-sign. As an

analogy for fading of lines in letters we have the top of the adjacent

B-sign; but there are a number of other faint lines on the sherd; for

example, the diagonal stroke in the top left corner; and there are some

marks in the top right corner. This was a milk bowl, we are told, and

maybe these are stains from liquids it previously contained; or it is a

palimpsest, and other writing has been washed off the surface, to make

space for this inscription.

Most damaging for the sun-and-snake

sign is an arc, actually a full semi-circle, running from the left side

to the right edge, passing through the door, the house, and under the

eye, thereby vitiating the uraeus serpent of the sun, and ending below

the ox-head, where it might have been interpreted as a NI syllabogram,

like the tusks on the Tuba amulets (Photos 2 and 3 here).

Consequently my total is eight letters, and if the `Ayin is correct,

it would support the editors' reading of their proposed top line as `BD;

but rather than a noun "servant" (`bd), I would construct a

verb, '`BD, "I serve", or "I till"; the utterance that emerges, with a

slight rearrangement of letters in the bottom line, is not at all fishy

but admirably horticultural:

'A `A BA DA GA NA TA

" I cultivate the garden"

As Voltaire's Candide would say, gardening is so necessary: il faut cultiver notre jardin.

This is a response that Adam (ha-'adam, the human) might have given to his commission to cultivate (`bd) and tend (sh-m-r) the garden (gan) of Eden (Genesis 2:15).

"Yea, verily, I will cultivate the garden".

For NA I have called upon the character next to the cross-sign; I have already rejected it as p,

the desperate measure taken by the editors; it is a cobra (Hieroglyph I12), in the pose

that it has in the proto-syllabary, but not in the proto-consonantary;

and this is my main reason for declaring this text to be syllabic, but

it is tentative and fallible.

One letter remains to be identified, in the bottom right corner: the editors reasonably saw it as n,

as this is (approximately) the shape of N in the Phoenician alphabet; but it is

reversed (back to front); the only example I know of this form is on the

Jerusalem jar, where I hesitatingly suggest that it represents NU in a

neo-syllabic inscription:

https://cryptcracker.blogspot.com/2019/05/jerusalem-jar-inscription-2.html

In the proto-syllabary the closest letter to this is MA, from maggalu,

"sickle". If we could read it on our sherd as a logogram, in some kind

of "instrumental" case, it might say: "I cultivate the garden (with) a

sickle". In response to this, I would raise two objections: sickles are

for mowing meadows and reaping grains; sickles have short handles, and

this feature is maintained on the MA characters displayed in the Byblos

inscriptions, though the scribe who engraved the two examples of MA on

the Megiddo ring did not restrain his stylus on this detail; but

they are the reverse of the character on this Lakish sherd

(though they will be the right way round when

impressed in clay and reversed).

https://sites.google.com/site/collesseum/megiddoring

Pursuing the horticulture theme,

we encountered the word gannat

(garden) on the Lakish five-sided sherd: the GA is much the same in

both texts; the Taw (TA or TU?) is a cross, somewhat defective on the

pentagon; there the NA snake has a head, with a doubling dot in it,

hence GANNAT; the new sherd has a dot beside the GA and above the Taw,

but this is distant from the NA. I will now propose that the two snake

figures on our sherd, even though they are apparently looking away from

each other, represent double NA (running from right to left). Having

said this, I was immediately struck by a another idea: the scribe is

mixing the syllabic and consonantal systems; so as to achieve the goal

of writing GANNAT, without having to include a "dead vowel", as was the

case on the pentagon inscription, GA N(A) NA T (though the NANA was

effected by a doubling dot in the head of the snake). Presumably the two

snake signs, N and NA, were written back to back to alert the reader to

interpret this sequence as N-NA. No doubt, this will be judged as a

typical bizarre conceit ejected from the Colless brain, but I dare to

say that it first occurred to the mind of the Lakish scribe who wrote

this with his brush and ink.

Is the statement a vow? "I will cultivate the garden".

There remains that dot or blob to the left of the GA: it must be a word

separater; there are only two words, and that is where the division

between them occurs; by the same token, the mark in the top right

corner, above the 'A, indicates the starting point of the text; so it

might be better to say that both markers indicate the beginning of a new

word.

What conclusion can we possibly reach in the presence of this conflicting data?

Is it a consonatal inscription? If it is proto-consonantal, the graphemes for D and H (or the rarer G and Z.) are not there to indicate this identification.

Is it a syllabic text? The neo-syllabary

can probably be excluded from the discussion, as it was a phenomenon

of the early Iron Age (1200-1000), and this object is firmly dated

around 1450 BCE. The D has no counterpart in the neo-syllabary, and

likewise the B. However, the pentagonal sherd and the triangular sherd

show that the proto-syllabary was employed at Lakish, but they both had recognizable proto-syllabic characters; the new sherd has only ambiguous graphemes.

We seem to be driven to choosing between proto-syllabic or early alphabetic (whether long or short alphabet is not determinable). Keeping in mind the fact that three quarters of the letters in the neo-consonantary are derived from the proto-syllabary, and one quarter of the syllabograms in the proto-syllabary are also found as consonantograms in the proto-alphabet,

we are faced with a set of signs that seem to belong to both systems.

If only the author had spoken a few more words, he might have made his

system clear to us, but he might have been deliberately tantalizing his

readers.

We have to start again, examining each of the letters and comparing their form with other Lakish examples.

From the top (the point of departure is marked by a blob in the upper right corner): the first letter is assumed to be consonantal 'Alep (glottal stop) or syllabic 'A; but the anomalous bovine horns (contrast the headless pair above the number 05 above) and the missing skull-line would drive us to see a pot (DU) or a bag (S.adey); nevertheless we have an analogy for the gap between the horns in the Theban desert (Wadi el-Hol, early proto-consonantal), and the convex horns (curving outwards) have counterparts on Sinai inscription 376, and on the Lakish lice comb..

Second,

the circular sign on the Lakish sherd (to the left of the ox), which is

sufficiently angular on each side to make it an eye with corners, and

thus representing the consonant `Ayin or the syllable `A. This sequence (added to our prior knowledge of what follows) suggests an exercise in tabulating letters that have -a in the proto-syllabary.

Here we need to remember that the majority of the letters of the early

alphabet were derived from the proto-syllabary, and most of them were -a syllabograms. To demonstrate this, the unmistakably proto-consonantal text from Egypt that is reproduced here in my drawing, may be transcribed as if it were proto-syllabic.

From right to left: RA BA WA NA MI NA HI NA GA THA/SHA HI 'A PU MI (HA) RA

The hank of thread (HA)

is not attested in syllabic texts, and is an indication that this

inscription is not proto-syllabic, nor neo-consonantal, but

proto-consonantal.

Pausing for a moment of reflection, we may ask

how the circle sign (whether dotted or not), which originally

represented the sun (shimsh) became a stylized eye (again with

optional dot, presumably for the pupil). I will tell you: I do not know.

God alone knows the truth. However, I could invoke Matahari: the sun in

the Malay language (Bahasa Malaysia, Bahasa Indonesia) is mata hari, "eye of the day"; hari, I presume, would be cognate with the fellow-Austronesian word râ in

the Mâori language, meaning "day" as well as "sun"; and even if we only

know Egyptian Ra` or Re` from crossword puzzles, we are aware of his

solar connection. The reason (I ween Germanically, rather than imagine

Romanically) for this widespread designation for the sun is the greeting

it receives at its morning appearing: Hurrah or Hurray (according to your social class).

Keeping all of this in mind (though drawing a darkening veil over the

latter attempt at illumination and enlightenment), we continue our

analysis of the new Lakish milk-bowl sherd.

The bovine `Alep is weird; and the Bayt (house) is unusual, a tall rectangle instead of a square, but it could function as B or BA.

The Dalet (door) has a counterpart on the Thebes inscriptions, but also the type with two panels (see Photo 11); it can be D or DA. Remember, the fish-sign is never D, but always S.

This collection of signs, if they are

syllabograms, produces a first person singular verb, imperfect tense; it looks

highly suspect as 'A`ABADA, but if "dead vowels" are muted and

suppressed, we have 'a`bad, which is reasonable, but still questionable,

and perhaps all the vowels ought to be ignored and the text regarded as

consonantal writing.

The blob apparently indicates the start of a new sequence, beginning with the throwstick, G or GA.

Here is a new thought: the scribe's intention was to have this long

letter begin a new line of writing, running from right to left. The next

character in his second sequence is the snake in the bottom right

corner, and this should be consonantal N; if it is syllabic, it would be

a misshapen MA (a sickle), but not NA. The normal proto-syllabic NA

comes next: the cobra with a kink in the tail.

Finally

we see a Taw; there is no doubt about

this identification, since the cross-sign stands for the sound /t/ in

all four

classes of early West Semitic scripts, and beyond. From the outset the

consonantal alphabet had a simple cross-sign for T/t/, consisting of two

equal lines (+ or x); but in the proto-syllabary this had not been the case: x was

the syllabogram for KU, and and the Taw cross had a long stem, and

consistently displayed this feature throughout the ages. Unfortunately

the Tuba tubes do not have any T-syllabograms, but all the early Gubla

(Byblos) texts follow this pattern, with the T- (sometimes on its side).

The verified proto-syllabic inscriptions that we have presented here

testify decisively to this fact: Lahun heddle jack [12], Puerto Rico figurine [4], Lakish pentagonal sherd [13],

and quite clearly on this alleged "missing link", the Lakish rectagonal

sherd (well, it has one right angle, but it is technically a trapezoid

quadrilateral, or vice versa).

Case closed. QED (as promised in

the prologue to this drama). The last two letters of the text (N- T-)

have the forms peculiar to the proto-syllabary, therefore this must be a

proto-syllabic inscription, even though the first five of the eight

letters (' ` B D G) could function as either syllabic or consonantal,

and the sixth is consonantal N. This might need to be classified as "a mixed syllabic and consonantal text". The transcription would thus be:

| 'A`ABADA | GANNATA

Affirmative: "I cultivate a garden"

Volitive (cohortative): "Let me cultivate the garden" (a wish or a prayer)

If this were Biblical Hebrew the verb would be, cohortative form: 'E`EBDÂ. If this is equivalent to the

'A`ABADA on the sherd (the BA syllable having a "dead" vowel, or the -a

stands for shwa), an explanation would be: in syllabic writing based on

the three vowels (-u, -a, -i), the vowel -e would necessarily be

represented by -a syllabograms; or we may simply say that the

introduction of additional vowels is a later development in Hebrew.

However, the final volitive -a has apparently been recorded in the

inscription, and although it could be ignored, by the rules of syllabic

transcription of speech, and classed unhelpfully as a "dead" vowel, it

may well correspond to the Hebrew volitive inflexion â (which is written with unpronounced -h to represent the a-vowel).

Incidentally, this GANNATA may be the same garden as the GAN(A)NATA in

the prayer on the pentagonal sherd. The question remains whether the

final -a is to be retained as significant or discarded as superfluous.

In the present instance it could be indicating the accusative case, the

garden being the object of the verb.

Finally, and perhaps conclusively, the sherd was found among the charred remains of organic matter, including barley seeds.

23/3/2022

https://www.academia.edu/s/24b120db88#comment_1089561

Another attempt at interpreting this inscription has come to my notice: Douglas

Petrovich, The Lachish Milk Bowl Ostracon: A Hebrew Inscription from Joshua's

Conquest at Lachish, Bible and Spade 35/1 (2022) 16-22. The title

indicates that great claims are being made for this little document: it was

dropped inside Lakish by an Israelian invader; the proto-alphabet was not known

in Canaan before then; it says, purportedly, "N, servant (`bd) over

(`l) honey (npt)"; this reading is invalidated by the P

(producing npt) instead of N, and the N (as an abbreviation or rebus of

the name Nahash, "snake") instead of G (in my reading, gannat).

Petrovich discusses Carbon 14 dating in relation to the sherd, and highlights

the charred organic matter, including barley seeds, at the site of the

inscription. My response would be: Is this the remains of a vegetable garden?

A notification of the Antiquity article (with the Misgav interpretation) popped up on the Academia website. I responded to it, and Douglas Petrovich reacted immediately (giving no indication of the discussion we had held about it on Academia in 2022) and reaffirmed his untenable position.

9/4/2024

Brian Edric Colless Massey University

Good to have this inscription to add to the treasure trove that Tel Lachish is yielding to excavation. Sad to say, the editors have no idea about its typology or meaning: it was found in a garden bed with barley seeds, and I think it reads '`BD GNNT, "I am growing a garden"; the two words have a dot indicating where they begin: the writing may be syllabic rather than simply consonantal.

https://cryptcracker.blogspot.com/2021/04/another-lakish-inscription.html

Douglas

N Petrovich Brookes Bible College

Actually, the inscription was not found in a garden bed. It was found at the

confluence of 3 loci, one being fill (above it), and another being destruction

debris (datable, do to organic material being part of the debris). Moreover, it

was located just inside the city wall. What's even more, and something that the

authors completely "whiffed on" (to use an American baseball

expression), is that it was located just opposite from a breach in the city

wall that almost certainly was created by the attackers who succeeded in

breaking into the city and both destroying architecture (e.g., the city wall,

and much more) and decimating the population. During the next sub-phase of

occupation, a short but final look at the LBA IIB, the city wall was in

complete disuse for this sub-phase, except for the squatters who were there and

using whatever they could (e.g., part of the city wall as 1 of the 4 walls of

their makeshift homes) to make ends meet. This has nothing to do with gardens

or seed beds. Meanwhile, the correct decipherment is ebed 'al nofet:

"servant in charge of honey" (a Hebrew inscription!!), as I have

explained in my article of 2022.

Brian Edric Colless

In your subsequent conversations with interested onlookers you rightly intimate that this is an ostracon, a piece of broken pottery used as a writing tablet, and the inscription is probably not about the original contents of the vessel. So it has nothing to do with milk; and you also declare that it is not about a garden, but about a honey man, apparently an apiarist,. I have to say, I do not believe your interpretation (`BD `L NPT, "servant over honey"), nor do I believe my own reading ('`BD GNNT, "I am growing a garden"), because the only one who knew the intended meaning was the person who wrote this inscription. Before this jamboree or jam session (with its arbitrary improvisations) began, you had 13 supporters (taking the honey bait), to my one (my beloved daughter Laurel, but one of my dear friends has now joined the fray). Nevertheless, I think your case is falsifiable. Anyone who wishes to follow this debate must go to your published article and get a good photograph of the sherd, and also your helpfully annotated but fatally inaccurate drawing.

(2022) The Lachish Milk Bowl Ostracon: A Hebrew Inscription from Joshua's Conquest at Lachish

As you well know, you and I are on the same side: we are both searching for evidence about "the children of Israel" in Egypt and in the Levant, and between us we have amassed a goodly heap of data. and if we could get our act together we could build a tower of truth.

You point to a hole in a wall which could have been made by the conquering army of Israel, allowing access to this city. You speak of squatters in makeshift homes, after the destruction, eking out an existence. Incidentally, that is just like the events of our own times, and my gardener would fit into that setting nicely: "Look, I have got a garden growing here in this mess". Alternatively, this garden was there with its little label when the invading force ruined the place (the "locus").

I called as witnesses the barley seeds; but you only want them for radiocarbon dating; they are not as appealing as honey, and you find a word NPT at the bottom, as did Misgav, and Goldwasser, in desperation, none of you knowing what that middle letter is. We both realize that the origin of P (Pe) is not a corner (as commonly claimed) but a human mouth [()], and it goes right back to the Proto-syllabary as PU, and as P in the derivative Proto-consonantary. That is not what we have here. Look closely. That is the form of serpent with a bend in the tail, as found representing NA (from nakshu "snake") in the Proto-syllabary.

Now please go here (this is very important):

http://cryptcracker.blogspot.com/2021/12/lakish-scripts.html

You are now looking at another sherd from Lakish, which was found for me by my son Michael, in the journal Tel Aviv (1976); in the top right area there is a comparable proto-syllabic snake, with a head, and a very angular tail; at the bottom there is another one, with a T-cross on its left, and a G-throwstick on its right; this is the same letter as the one in the middle of the milk-bowl inscription, which is simply brushed aside by Doug, as possibly the initial letter of the name of his "Minister of Apiculture"; but he wrongly takes it to be another snake-sign, hence a false N. In the pentagonal sherd, the word gannat (garden), has the N doubled with a dot, as in the Hebraic gannah (this is a general practice in ancient West Semitic writing, and that is something we worked out together, Doug). What our gardener scribe has done to achieve gannat seems to be this: first write the consonantal N-snake, and then the proto-syllabic NA, hence GANNAT.

Doug has overlooked the two dots I mentioned. The first dot is in the top right corner, next to one of the horns of the ox (they are misshapen but this is an alep, and his `al collapses like the Baltimore bridge). So that is where the text begins. The second dot is next to the throwstick, but Doug merges it to form a head for his snake; it indicates the start of the second and final word.

Accordingly, the reading is '`BD (I cultivate) GNNT (a garden), just like Voltaire's Candide; but `bd is the very verb used in Genesis 2:15 for cultivating the primordial garden (there gan rather than gannah); but that does not mean that our inscription is Hebrew; it is merely West Semitic.

For the first time in my long

life of 88 years I made a New Year's resolution: in 2024 I will ruthlessly

expose the "alternative facts" that have been created in this field

of West Semitic "palaiogrammatology". A massive paradigm shift is in

progress: Vive la Quadrinité!

E=(2M + 2C) squared

I have a spoonful of New Zealand

maanuka honey every day, and if you are still hankering for a taste of NPT or

DBSh, I can offer you the elaborate apiary of Reh.ob, along with fig syrup, the

prophet Elisha`, and a mongoose.

http://cryptcracker.blogspot.com/2020/10/ancient-rehob-and-its-apiary.html

While I slept, the bees have still been buzzing about the honey pot that is not there, while the garden that offers many more delights is being overlooked. The word NPT is a fiction; if it was present it would indicate that the language of the text is classical Hebrew; other Semitic languages have NBT, and the only possible cognate word in Arabic means spittle or vomit. Douglas has no way out of this viscous mess he created, along with all the others in the field of West Semitic palaiogrammatology. As I have intimated, their sins will find them out, and it is my thankless task to bring all their fake news into the bright light of accuracy and honesty. They have all been particularly obtuse in applying the archaeological clues to the Sinai Proto-consonantary inscriptions, starting with metallurgy (and Douglas Petrovich is also a transgressor in this regard). The nonsense they blithely extract from these illuminating texts is published in prestigious journals with the blessing and approbation of their peerless peers.

http://cryptcracker.blogspot.com/2007/11/ancient-metal-melting-sinai-inscription.html

Have you noticed that we now have two ostraca from Lakish (Tel Lachish, Tell ed-Duweir) that speak of a garden? Here is the horticulture set of tablets from Sinai:

http://cryptcracker.blogspot.com/2007/10/ancient-sinai-horticulture-sinai.html

Ye are a stiffnecked people" (Moshe Book 2 = Shemot = Exodus 33:5). Prepare for a rebuke from your elder. I am as old as Moshe was at that time (I was conceived in 1935), and I have had vast experience of ancient scripts and texts. Therefore I say unto all of you: when we are confronted by an ancient inscription none of us knows what the writer's intended meaning was/is. But here you are defending the NPT 'honey" interpretation, which the "principial editors" (so to speak) foisted upon us in their ignorance. The crisis in West Semitic epigraphical research (it is a scandal, actually) is caused by earnest scholars who can read the Phoenician royal inscriptions, the Moabite stone, the military messages from Tel Lachish, that is, the WS consonantary of the Iron Age, and who think they can understand Bronze-Age WS inscriptions, and find their way through the maze that I call the Quadrinity. None of you (I recognize that the people who need this "eldering" are out of range) have trod this road less traveled, but Doug has creditably come to accept that the Protosyllabary preceded the Protoconsonantary, and he is rightly affirming that the letters of the protoalphabet could be used as logograms and ideograms (and rebuses), as in the Egyptian system; throughout the era of the Quadrinity, the tricks of the trade were not discarded; until the Phoenician consonantary and the Greco-Roman alphabet held sway. I showed that LBO (Lahun Bilingual Ostracon) to DNP, when he was working on the two books, and he accepted that the B-house character could stand for the whole word. So the generalities are good, but some of the details he proposes are disastrous.

We have to put this honey-pot in a safe place, where it is out of sight, and unable to tempt us: my jar of Maanuka honey is in a cupboard, enclosed in a canister, to keep the ants away. If others want to turn that central G sign into N, and allow the dot to double it (rather than indicating where the second word begins), they are at liberty to do so, but they are idiots. Incidentally, Doug has trouble with the throwstick as gaml > gamma (it is not on his table of signs); but if this one is read as N, there are now three serpents, four already with the dot, and we are in a snake pit, and our "Minister for Apiculture" has become a snake-charmer or a Doctor of Herpetology. The sequence of consonants is GNNT, "garden", with the first snake-sign consonantal, and the second proto-syllabic, and I have shown you another Lakish inscription with proto-syllabic characters where the word gannat is written GA-NNA-T- by putting a doubling dot in the head of the NA-snake (from NAkhash, "snake"). With Hebrew NPT dismissed, there is no justification for thinking that these words ("I am cultivating a garden") were written by an interloper who left his "Hebrew" calling card, identifying himself as a "honey-man". The supposed P can not be a mouth-sign: it is roughly [ ___( ] and not [ ___) ]. The letter P in Sinai and Hol inscriptions will be examined in a separate posting.

Meanwhile, this way to the delights of the Quadrinity Garden:

https://cryptcracker.blogspot.com/2021/04/another-lakish-inscription.html

Douglas Petrovich responds, defending his indefensible reading NPT

You wrote this: "The word NPT is a fiction; if it was present it would indicate that the language of the text is classical Hebrew; other Semitic languages have NBT, and the only possible cognate word in Arabic means spittle or vomit. Douglas has no way out of this viscous mess he created." Nice try, Brian, but you are wrong and badly wrong. If NPT is present, it certainly does scream out at the reader that the author composed his (purely-consonantal, yet non-syllabic) inscription in Hebrew, the same Hebrew that was used for the composition of the biblical text. This is true. However, it should not scare away anyone, because pictographic-alphabetic Hebrew inscriptions were being composed already for over 530 years by the time that this one was composed. The whole point is that NPT reveals the language behind the inscription to be Hebrew. Now to your well-intended but error-plagued analysis of the word NPT.

As for H7 on the LMBO (see my published article for its careful and correct electronical drawing), it indeed is the corner of a mouth, which signifies the P letter. The P-letters on alphabetic inscriptions of the New Kingdom at Serabit el-Khadim that date to the first half to middle of the 15th century BC routinely (if not always) feature the entire mouth (see my alphabetic chart, a free download from my academia.edu page). However, the use of the entire mouth had disappeared by the time we reach proto-alphabetic inscriptions of the Late Bronze Age II, such as the corner-of-the-mouth one that appears on Sass's Lachish Jar Sherd. The Lachish Jar Sherd's and the Izbet Tsartah Ostracon's P-examples are nearly indistinguishable from our H7. Misgav correctly understood this when evaluating the LMBO, and you have no firm ground on which to stand in opposition, no matter how much steam you expel while saying so. In fact, the P-letter in its post-full-mouth state confirms the 14C evidence's dating of the ostracon's deposition to the last quarter of the 15th century BC. Palaeography verifies that this form of the (H7 mouth-)letter dates the inscription to shortly after the state of the alphabet at Serabit, where inscriptions stop being composed within the reign of Amenhotep II (1446 BC, technically).

Akkadian and Ugaritic indeed write NBT instead of NPT. Akkadian used NPT for the honeybee, and by the time of Ugaritic, the Ugaritians were using the word for the sweet and thick honey, itself. What you may not know is that a singular use of the NPT spelling is found in a later Punic text, although the damaged state of the text makes it difficult to understand the context completely. Either way, Punic enclaves did not appear until Canaanites migrated westward early in the Iron Age, which long postdates the composition of the LMBO, so on account of Akkadian's and Ugaritic's use of a completely different script, NPT on the LMBO must be composed in Hebrew. We should not be surprised with this difference (i.e., Hebrew's distinct spelling of the word, in contrast to the spelling used by its Semitic cousins), because this represents the well known B→P shift of antiquity.

There is no need to call this inscription alphabetic AND syllabic. It is purely alphabetic, following exactly in the shoes of its predecessor-inscriptions from Egypt and Sinai of 50 years earlier and beyond (except for P's change from a full mouth to the corner of a mouth, of course). The LMBO has 3 distinct AND SEPARATED words, along with an outlier (centered!) N that can be understood only after correctly reading the inscription, interpreting its use as an official title (which convention the Israelites understood and used for themselves while living in Egypt), and realizing that the N can represent only the name of the "servant in charge of honey" who was part of the army that invaded Lachish, destroyed the city, and killed off its inhabitants, as the archaeological context confirms in spades. There are no painted "dots" on the inscription, either. What you are confusing with dots is the randomly better preservation of ink at certain places on the ostracon where the ink that created the text originally was applied. Cheers, mate!

Brian Colless

Unfortunately, my cheer-full mate Douglas has taken refuge in a vast vat of

viscous vitriolic vituperation, and has now immersed himself in black molasses

instead of wholesome honey. Yet he was offered the option of entering a

glorious garden, like the one in the beginning: "Yahwe Elohim planted a

garden in Eden" (Genesis 2:8), and put the Human he had created "in

the garden (gan) of Eden to cultivate (`bd) it" (2:15). But there was a

wily serpent (nakhash) in that garden (3:1), and Douglas is alert to its wiles,

and he will not be seduced into recognizing its presence; that letter H7 has to

be a gaping mouth uttering the plosive sound /p/. But if you have a keen eye to

spot them, you might see six snakes swarming in that bowl. My old peepers have

been diagnosed as very healthy, although somewhat myopic, but that is helpful

for close work, such as reading fine print and scrutinizing ancient

inscriptions.

https://www.academia.edu/73154914/_2022_The_Lachish_Milk_Bowl_Ostracon_A_Hebrew_Inscription_from_Joshuas_Conquest_at_Lachish

For our snake-hunt we need to refer to the Petrovich drawing

and photograph, under a bright light

(1) Bottom right corner, the one that is on the way to producing the N of

the Greco-Roman alphabet (as in DNP's middle name), but it has a long neck; no

problem, this is indubitably an early-alphabet N.

(2-3) Top right corner, two rearing serpents, if you like; but Douglas

practises plastic surgery, and turns the upper one into a round eye; he ignores

the troublesome dot to the left, but if it is accepted in the same way as he uses

the other strategic dot to the left of the central character, a snake emerges

from the haze.To construct his circle he has only one little arc with the

half-circle on the right added in pink, but at the top there is a clear gap

that has to be inked in, but he boldly chooses black instead of pink. Strike me

lucky, or pink, what a way to achieve your own goal; but this is an "own

goal" of the soccer football kind, and it counts against your score.

Similarly, the tail of the lower letter (3) strays right outside the frame. One

trespass we might overlook, but two trespasses we will not forgive. This is not

`Ayin and Lamed saying `al ("over"), but it must be an ox-head

(albeit with an unusual pair of horns), and the right side of its head is

apparently inked onto the broken edge; in any case the letter is inside the

boundary.

(4) The character in the middle is perceived to be a snake, and the significant

dot beside it is added to it as its head. If we look for a corresponding

Egyptian hieroglyph, serpent-signs are available; this could not be a cobra

(I10 or I12, which feature in the bottom line) or a snake with two angles in

its body (I14), so it has to be a horned viper (I9), but the body of this

letter is far too long for a viper, and it has no horns. It is a throwstick,

and therefore G or GA; unlike the snakes, it can be presented in any stance.

http://cryptcracker.blogspot.com/2015/12/lakish-jar-sherd.html

This inscription has been mentioned in dispatches, so let us give it an honourable burial.

It was inscribed on the clay before firing, so it is not an ostracon; its text relates to itself and its contents, I suggest, not to an owner (PKL SPR Pikol the scribe).

The probable interpretation is: Pot (pk) for (l) measuring (spr) 5 hekat

There is a numeral: the 7-shaped sign is understood as Hieratic 5, and it is accompanied by the Egyptian sign for a grain-measure.

I have not published it officially, but eventually people will lose their fear or disdain for being my co-author. It has happened in other fields in which I have worked.

The idea of measuring (spr) grain, is used in connection with Yosep in Genesis 41:49.

There are two clear instances of P, and they have their bend at the top, as in the Phoenician alphabet.

You need one that bends at the bottom for your despairingly desperate NPT.

I notice that this message is addressed to me, so I am just talking to myself, as I do all the time, here in my hermitage on the hill.

While he yet spake there came a great multitude,

saying: "How judgest thou the new document from the time of the Judges

bearing the name of Judge Jerubbaal?"

He answered them not, saying: "Perverse generation, judge not, lest ye be

judged; ye know the judgements and rules of this contest, which have already

been revealed unto you. First ask the question: Are you syllabic or

consonantal?"

https://cryptcracker.blogspot.com/2021/09/khirbet-ar-rai-inscription-lyrbl.html

1 comment:

Post a Comment