[V] "Feast (MShT) of the supreme (R) celebration (H) of `Anat (`NT). 'El ('L) will provide (YGSh) [H] plenty (RB) of wine (WN) and victuals (MN) for the celebration (H). We will sacrifice (NGTh) for her (H) an ox (') and (P) a prime (R) fatling (MKh)."

At the end of the discussion, a different meaning will be proposed for the first word (MShT).

(Another early West Semitic inscription about celebratory feasting for the Goddess is here.)

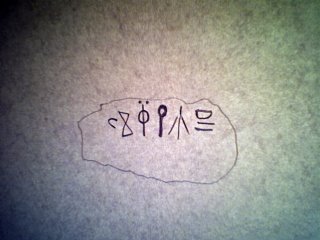

These are my own drawings, but photographs are available on the internet here.

These two inscriptions are among the most intriguing discoveries of recent times: they show us the alphabet as it originally was, pictorial, or pictophonic (images representing sounds), with an ox-head (A. 'Aleph, Alpha), a human head (R), an eye (`Ayin), a mouth (P), a boomerang (G), and many more picture-signs. They were found by Yale Egyptologists John Coleman Darnell and his wife Deborah, on a desert road near Thebes (Luxor), on a rock-face in the Wadi el-Hol ('Terror Gulch"). When they were first announced (New York Times, 13th-14th of November 1999) it was claimed that they were the oldest known alphabetic texts. However, other examples had previously turned up in Sinai and Syria-Palestine, and also elsewhere in Egypt, so the competition for being the earliest is fierce. Notice that I have registered these as Thebes 8 and 9, because other cases of proto-alphabetic writing had already come to light in the region of Thebes in Upper (Southern) Egypt, but these have been ignored in books written about the origin of the alphabet.

I began commenting on the the Wadi el-Hol proto-alphabetic material immediately after the first newspaper reports appeared (ANE forum), as it provided an opportunity for testing my own table of signs, constructed on the foundation of my readings of the Sinai inscriptions (Colless 1988 and 1990). Since then I have put a number of postings on the internet (on the ANE [Ancient Near East] discussion group).

An encyclopedia article is available on the subject (not written by myself, please note, and much of it is now consigned to the underworld of the discussion), which includes an outline of my views (based on my ANE internet postings) and a table of the original letters of the alphabet (according to my understanding, showing the Egyptian hieroglyphs that were borrowed to create the letters). My own table of the development of the signs is available on the web, and at the end of this essay, below.

What follows here is the culmination of my musings on the identity of the various signs, including a suggested translation of the inscriptions.

Actually, I think this is an example of 1 + 1 = 1 : there is one proto-alphabetic inscription, running down, then across to the left (so it is "one multiplied by one", 1 x 1 = 1). In my interpretation they talk about the same thing: a celebration for a goddess, and at the join the text has: [V] ... God will provide ... [H] plenty of wine ....

Notice that there is in fact a dividing line at the point of separation of the two statements.

A case can be made for single authorship: both the ox-heads have a line for the mouth, and this is somewhat unique; the boomerangs (G) each have one end open; the three heads (R) differ from one another; the snakes (N) are vertical on the horizontal line, and the snake on the vertical line is horizontal; but the two instances of the rejoicer (H) on the horizontal line do not share the same size and stance, so differences can not be decisive in this matter.

(Another early West Semitic inscription about celebratory feasting for the Goddess is here.)

Before we embark on decipherment, we always have to remind ourselves that only the person who wrote a particular proto-alphabetic inscription knew what it said and meant (what he/she meant it to say, with no separation of words, and no vowels registered, only consonants).

But first we need to identify the letters: a controversial procedure, and a daunting task. We begin with the vertical sequence of signs [V1 - V13]. Actually the characters move obliquely leftwards, presumably making their way to link up with the horizontal text [H1 - H16].

However, this inscription is accompanied by a drawing (on the left of H), which must be included in the discussion. I have already ruminated over this image elsewhere on the web, but it comes down to this: while this figure certainly resembles the Egyptian sign for 'life' (`ankh), it is better to see it as a goddess; the deity TNT (Tannit) is represented by a similar symbol in later West Semitic iconography (with forearms raised), and the name TNT is already found on a Bronze Age statuette from Sinai (347, in the temple of the turquoise miners at Serabit el-Khadim). Apparently there are two snakes (horned viper and cobra) denoting double N, in line with "Tannit".

This person has a crook-like object hanging from the left hand (and I have been tempted to include it in the inscription, as a letter); it is probably hieroglyph S29, a piece of folded cloth (standing for s in Egyptian writing). Gardiner notes that it is often seen in the hands of statues, and was probably used as a handkerchief (as with trumpeter Louis Armstrong and tenor Luciano Pavarotti). Presumably it shows that the person is important. Another detail is the head, which is large in proportion to the body, as if a child is being depicted. This may be deliberate, as an Egyptian celebration for the birth of Hat-Hor is attested (Darnell 2002, 137). A feast for a divine infant is analogous to Christmas, likewise with copious consumption of food and drink. (Speculation: Tannit, mentioned above, whose symbol has this form, is associated with the death of infants, natural or sacrificial?)

This person has a crook-like object hanging from the left hand (and I have been tempted to include it in the inscription, as a letter); it is probably hieroglyph S29, a piece of folded cloth (standing for s in Egyptian writing). Gardiner notes that it is often seen in the hands of statues, and was probably used as a handkerchief (as with trumpeter Louis Armstrong and tenor Luciano Pavarotti). Presumably it shows that the person is important. Another detail is the head, which is large in proportion to the body, as if a child is being depicted. This may be deliberate, as an Egyptian celebration for the birth of Hat-Hor is attested (Darnell 2002, 137). A feast for a divine infant is analogous to Christmas, likewise with copious consumption of food and drink. (Speculation: Tannit, mentioned above, whose symbol has this form, is associated with the death of infants, natural or sacrificial?)

Moving now through a survey of all the signs. In this exercise, the reader will need a photocopy of my annotated drawings (available right here or elsewhere on the web, I notice).

V1 (Darnell 2.1 m) M

No problems here: this is the Egyptian water sign (n), and it yields M acrophonically from West Semitic words for water (mu, mayim). There are two more examples (Darnell says three) in the horizontal line (H5, H14, but not H10).

V2 (D 2.2 th) Sh

Great uncertainty here: for Darnell and his team (and also Hamilton) this is a "clear and unambiguous" case of the Egyptian hobble-sign (standing for the sound tch, and conventionally transcribed as underlined t); and yet it is admitted that it has "an odd vertical orientation" and it is "shortened from its normal length"; in addition, both cases of this letter (V2 and V11) have a larger circle on the left, whereas the standard form has two small circles, one immediately above the other and almost touching each other; therefore the hobble is not a good candidate. When I first looked at it, I immediately compared it to the sign for Sh. It had long been my opinion (now acknowledged by Stefan Wimmer) that in the three West Semitic scripts (syllabary, consonantary/ proto-alphabet, and cuneiform alphabet) the word for "sun" (shimsh) had been the acrophonic agent for Sh: as a circle, or sun-disc with the uraeus serpent guarding it, or simply the snake without the disc (see examples on my table). Here (V2 and V11) the serpent has no tail, but the larger circle would represent the sun and the smaller circle the head of the snake. Darnell compares what we see here with South Arabian Th [o-o], and rightly so; but what must have happened in the borrowing of the proto-alphabet in Arabia is that the breast-sign (\/\/ from Thad 'breast', sign 10 on the horizontal inscription) has been used for Sh, and the sun-sign for Th. However, here we see a form of hieroglyph N6 (with the short tail omitted); but Alan Gardiner (who catalogued the characters of the Egyptian writing system, and was the first scholar to notice the connection between them and the letters of the alphabet) has N6 first appearing in the New Kingdom (Late Bronze Age), but Darnell argues that the Hol inscription belongs to the Middle Kingdom (Middle Bronze Age). Actually, the sun is sometimes portrayed in Middle Kingdom iconography with a serpent but without the tail. The typical form in the Sinai proto-alphabetic inscriptions is the sun with a serpent on each side (N6B), but the sun-disc is (apparently) omitted!

Refer to my Israel in Goshen.

David Vanderhooft has also made a pronouncement on this letter (2 and 11).

Wadi el-Ḥôl Inscription 2 and The Early Alphabetic Graph *ǵ, *ǵull-, ‘yoke’

Vanderhooft experienced a eureka moment when he saw a double ox-yoke, and connected it in his mind with this sign, and with the West Semitic word `l "yoke", which would originally have had initial Ghayin, as in Arabic; but each of the two instances of this sign has a larger circle on the left; the yoke has equal-sized rings. Moreover, Gh has already been identified in those informative Thebes tablets (1, 2, 3) and on a plaque discovered in Puerto Rico; it is derived from ghinab "grape", represented by a vinestand with grapes, which can be matched in the Arabian scripts; but it is not attested in a proto-alphabetic text yet. In my first published article on the origin of the Alphabet (Abr-Nahrain, 26, 1988, p. 63) I suggested Ugaritic GNB "grapes", taken together with the South Arabian letter G, and the Egyptian vine-hieroglyph (M43). On a scale of frequency of use (measurable in Ugaritic texts) Ghayin is in position 24, as opposed to 11 and 12 for Sh and Th; therefore it is unlikely that Ghayin would appear twice in a short inscription; the two words that he offers to justify its presence are suspect, and one of them has the throwstick as P instead of G.

V3 (D 2.3 t) T

The letter T (see also V8) is a simple cross (plus sign +, sometimes a multiplication sign x), and it goes by the name Taw, which means an identification mark, or the signature of an illiterate person. Here Darnell tacitly admits that no corresponding hieroglyph can be found, though Hamilton tries to find its origin in Z11 (also Z9 and Z10: X), apparently two crossed planks, or sticks, but not a taw). I think T, W, and Z did not have an Egyptian original.

V4 (D 2.4 r) R

This is a human head, and (beyond controversy) it is known to represent the consonant R, after the word ra'ish or rêsh, meaning 'head'. There are two other examples, at the beginning and end of the other line (H1, H16). No facial features are shown (in contrast to the Sinai examples with hairline indicated), but we may assume that all three heads are in profile, not front or back view. All are different, and this is not helpful to the view (strongly maintained by Darnell, and Hamilton) that an Egyptian prototype is being copied faithfully; rather it seems that to write the letter R you simply drew a man's head.

V5 (D 2.5 h) H

There are three examples of H (Darnell accepts V5, H7, H11 as H); the pictograph shows a person dancing (but, in a perhaps misguided endeavour to find a perfect match with an Egyptian hieroglyph, Darnell wants it to be "a seated man with hand to mouth" or even "a seated child" making the same gesture). But, as with R (the head), all three examples are different. My opinion has long been that the figure depicts a person jumping for joy, or dancing in celebration, and the Semitic root hll (as in Halleluyah) is involved (specifically the word hillul 'celebration'). Typically both forearms are raised and pointing to heaven (as in H7, corresponding to Hieroglyph A28, 'jubilation') but one arm may be up and the other down (as in H11 and here, V5, more reminiscent of A32, a person dancing, likewise denoting joy and jubilation). Ultimately, when the body had dropped off, this became E in the Greek alphabet. Note also that inverted examples can be found, with the person standing on his hands or head (Sinai 358, like Hieroglyph A29).

V6 (D 2.6 `) `(ayin)

The guttural consonant ` (named `ayin, and thus indicating its origin in an eye), appears only once in the inscription (H13 is not an eye but a mouth with two closed lips, and so P).

V7 (D 2.7 w) N

Uncertainty descends again, but my choice is for a snake, either a viper or a cobra; both are found representing N (from nakhash, 'snake'); in my interpretation H3 is the example of W (Darnell says it is L), and there are three other snakes (H4, 6, 8) all of them erect, or else turned sideways to fit the text into the available space, as with the M (H5, 14; contrast V1), the P (H13, mouth), the Th (H10, breast). The snake here (V7) could depict a cobra with its neck and head, but lying on its side, to conserve space, whereas the upright cobras in the other line are normal. An analogy of N with a straight vertical body and a head occurs on the Gezer sherd. Eventually the snake will assume the shape of N in the alphabet.

V8 (D 2.8 t) T

The second of the two instances of T (see V3 above).

A horizontal line runs below the T. It could be a simplified snake-sign (another N). Or it is a divider, and in my interpretation it separates the heading (V1 - 8: `Anat celebration) from the main statement (V9 - 13, H1 - 16, describing details of the celebrations).

V9 (D - ) Y

Darnell and his team have overlooked this character, and they do not show the dividing line, either; but Hamilton has both on his drawing, and he opts for Y, as I do. Y is usually a hand with its forearm (yad, or yod), viewed from the side, while K (unfortunately not present in this text), still known by the name Kap ('palm of the hand'), shows fingers (three or more).

V10 (D 2.9 p) G

Darnell and Hamilton do not accept this as a boomerang, and hence as G (from gaml, 'throwstick'), but follow the erroneous line that it represents P (pê), a corner (Hieroglyph O38, a right angle, a corner of a wall). For my part, the true P is H13, a mouth. The other G is H9, and neither of them is a right angle. Both could well represent a bend in a wall, and the fact that they have an open end suggests continuation of a wall; but they may also be showing the blade of a boomerang, viewed from above.

V11 (D 2.10 th) Sh

This is a counterpart to V2 (the sun with its serpent).

V12 (D 2.11 ') '(alep)

The ox-head is the sign for the glottal stop ('), and it finally emerges, upside down, with its horns as legs, at the beginning of the Greek alphabet, as the vowel A, named Alpha (from 'alep, ox). An interesting feature is that in this example, and its twin (H12), the mouth is distinctly marked, and this detail is not found on any of the examples from Sinai, as far as I can see. The fact that the human mouth (H13, P) has an unusual lip line supports my unfashionable understanding of it as P.

V13 (D 2.12 l) L

There has been general agreement from the outset that this a case of L, and that in combination with the preceding 'Alep it forms the word 'l, meaning 'god' or 'the god El'. However, there is doubt whether it represents a shepherd's crook (Hieroglyph S39), as I and others have assumed, to go with the name of the letter, Lamed, from the root lmd, learn, teach, train. Darnell and Hamilton connect the sign with Hieroglyph V1, a coil of rope; this could likewise be connected with training animals, and the possibility is that they are allographs, graphic alternatives (as opposed to graphic variants, meaning different ways of drawing the same character). Be that as it may, this would be the only case of L in the inscription, though Darnell and Hamilton have H3 also as L; Darnell's drawing shows it as a clear counterpart of V13 (though inverted), with an opening; but Hamilton and I see the head of H3 as closed, and for me, that means it is W.

H1 (Darnell 1.1 r) R

See the note on V4, and compare also H16.

H2 (D 1.2 b) B

This is the only instance of B, and the form is slightly unusual; for one thing it is turned on its side (like several other letters in the line; see the note on V7 N), but it is from this version that the Greek Beta will be made. The character represents the ground plan of a simple dwelling (bayt or bêt, house), usually a square, normally with a gap for the entrance (Hieroglyph O1), but sometimes a porch is added. The sign we see here is like Hieroglyph O4, a field-house, or reed-hut,

H3 (D 1.3 l) W

The sign for W is rare but it is usually a circle on a stem (-o), the same as Q in its later development, but Q is -o-; Darnell has V7 as W (N in my view) and this (H3) as L; but as noted under V13 (L), the sign here has a closed head, and should not be L (as either a crook or a coil).

H4 (D 1.4 n) N

This is an upright snake (nakhash) and therefore N; also H6 and H8; see the note on V7.

H5 (D 1.5 m) M

See the note on V1, and compare also H14; H10 is Th, not M).

H6 (D 1.6 n) N

See the note on V7, and see also H4 and H8.

H7 (D 1.7 h) H

See the note on V5, and compare also H11.

H8 (D 1.8 n) N

See the note on V7, and see also H4 and H6.

H9 (D 1.9 p) G

See the note on V10.

H10 (D 1.10 m) Th (Hamilton th/sh)

This would not be M, because it has only two angles; the three instances of M (H1, V5, V14) have three or more waves. It represents female breasts (thad), and is the source of Phoenician and Hebrew Sh (covering Th and Sh together), and as we can see from this example, it will become the Greek letter Sigma. See V2 above for the Sh-sign.

H11 (D 1.11 h) H

See the note on V5, and compare also H7 and H11.

H12 (D 1.12 ') '

See the note on V12.

H13 (D 1.13 sh) P

This is a good example of a human mouth (pu) representing P; it is in a vertical stance, but the lip line (unique among the few attested cases) makes its identity clear; see under V12 for the point that the ox-signs also indicate the mouth, an unusual feature.

H14 (D 1.14 m) M

See the note on V1, and compare also H5.

H15 (D 1.15 kh) Kh

This is a double helix, and it possibly represents a skein of thread (khayt 'thread') or a wick of twisted flax (kharam, Hamilton); the Egyptian hieroglyph stands for Hh [h.] not Kh [h_].

H16 (D 1.16 r) R

See the note on V4, and contrast H10 (Th).

TRANSCRIPTION

Vertical: M Sh T R H ` N T Y G Sh ' L

Horizontal: R B W N M N H N G Th H ' P M Kh R

TRANSLATION

VERTICAL

VERTICALM Sh T R H

If we divide this sequence into two words, we have Moses (MoShe) and the Law (ToRaH). This is a seductive reading but quite impossible. We can play with the many possibilities, but I have been saying right from the start (November 1999) that the first word on the down-column is M-Sh-T (the predecessor of Hebrew mishteh, banquet, symposium, from the root Sh-T-Y 'drink') Samson made such a feast, and it lasted seven days (Judges 14:10-12).

Support for this 'drinking-party' interpretation can be found in the Egyptian graffiti from the same area, apparently referring to holidays with drinking and eating feasts for the goddess, as reported by Darnell; there it was Hat-Hor, here it is the West Semitic goddess `Anat, named in V6-8 (`NT), and depicted with her handkerchief.

The intervening R and H are puzzling. A solution would be to interpret them as logograms, that is, the head says ra'ish (not simply R) and the jubilater stands for hillul, 'celebration' (not just H). In Hebrew the word ro'sh ('head') can also mean chief, top, first, and beginning. So, R H could say 'beginning of the celebration'; or the head could modify the feast as 'first', or 'top'.

Putting it all together, one possible translation would be:

"First-class feast for the celebration of `Anat".

However, the literal meaning of m-sh-t- is 'drinking place', and, in discussing the details of this site, Darnell (2002, 134-135) suggests that this could have been an official "drinking place" for the consumption of wine and beer in the celebrations for the goddess. This idea is supported by my reading of this inscription; indeed it seems to provide verification of my interpretation of the sequence of signs. The occurrence of 'plenty of wine' at the start of the horizontal line gives additional confirmation.

Accordingly, an alternative translation needs to be offered:

"Drinking-place for the super celebration of `Anat"

Y G Sh ' L

The sequence 'L was immediately recognized as 'god' by all who saw the inscription, and as probably indicating the chief god 'Il, or 'El in the Bible. In the past I have noted that GSh could be a word for 'army' (found in Arabic and Hebrew), and this suits the known circumstances of soldiers stationed on the desert road from Thebes; hence "the army of the god 'El".

Another possibility lurking there is: "the voice (gu) of (sha) God ('il)" .

However, the whole combination could be a personal name, Yigash'el (like Yisra'el), the signature of the writer.

Nevertheless, sense can be made of YGSh as a verb from the root n-g-sh 'approach, draw near'; in the h- causative form, and with the n dropped by assimilation to g, it could mean 'bring in, present'. An example is found in Genesis 27:25, where Jacob brings (wygsh) game for his father Isaac to eat, and wine (yayin) to drink (root sh-t-y, as in MShT above). The rock is pock-marked, but there is possibly a dot in the boomerang, indicating that the consonant G is doubled; this feature is observable at the Sinai turquoise mines, where the phrase "beloved of Ba`alat" (m'hbb`lt) is sometimes reduced to mhb`lt, with a doubling dot in the B.

"El will provide ...." (The objects of the verb can be found in the next line)

HORIZONTAL

R B W N M N H

The across-line begins with RB WN 'plenty of wine'; the RB corresponds to Hebrew rob, 'much, plenty', and WN goes with Ugaritic yn and Hebrew yayin, which would have developed from an earlier form *wayn (difficult to document, but found in Arabic as wayn 'vineyard, grapes', and early Greek woin- 'wine', and ultimately Hittite wiyana 'vine'). This might be the earliest-known instance of the international word "wine"(18th century BCE). Note that Hamilton sees a yod below H3, and this could make the word wyn, but he reads it as yln.

MN

I would like this to mean 'provisions' (food to go with the wine). Possibilities are: min, 'from'; mina, a measure of weight; manna, 'bread from heaven'; mnh 'portion', though mnt would be expected in the Bronze Age, but its use in the Hebrew Bible is interesting. In the Book of Esther we see the King of Persia giving a banquet (1:5, mishteh, as in V1-3 above); he provides Esther with her 'portion' (of food, rations, 2:9); and on a holy day of rejoicing the Jewish people distributed 'portions' to one another (9:19-22, cp Nehemiah 8:10-12); and 'portion' was used in connection with meat offered as sacrifice (Exodus 29:26, 1 Samuel 1:4:4-5); that seems to be in evidence here (an ox and a fatling are apparently mentioned at the end of this line). Arabic has a root MWN 'provision', mûna(t) 'provisions', Old S Arb mwnn 'victuals, provisions'.

H

This could be the third person pronoun suffix, 'his' or 'her' (portion); or the hillul logogram again (as in V5), hence:

"provisions for the celebration".

NGTh

This root means 'seek' in Ugaritic (`Anat searches for Ba`al when he disappears), and here it might mean something like 'supplicate'; but there is possibly another N-G-Th denoting 'sacrifice'; the word MGTh refers to something that is slaughtered for King Krt (16.6.18), parallel to 'imr 'lamb', perhaps related to Hbr muggash 'sacrificial offering'; or else 'a fat lamb'. Again, as with YGSh in V 9-11, the n of the root would be assimilated to g, and there is possibly a doubling dot here as well as there.

"We will sacrifice"

H

Pronominal suffix relating to 'him' ('El) or 'her' (`Anat), and presumably dative rather than accusative.

"for her"

' P M Kh R

The 'alep (ox-head) could be a logogram: 'ox' as the object of the verb. The P might function likewise, 'mouth'; or simply represent p, 'and' (copula, known in Ugaritic, for example). MKh would go nicely with Hebrew MeaHh, 'fatling'. The final R could have the same function as in V4: "super celebration" there, and here (in a context of animals for food) "a prime fatling".

Putting the pieces of this line of interpretation together, the result is:

[V] "Drinking-place (MShT) of the excellent (R) celebration (H) of `Anat (`NT). 'El ('L) will provide (YGSh) [H] plenty (RB) of wine (WN) and victuals (MN) for the celebration (H). We will sacrifice (NGTh) for her (H) an ox (') and (P) a prime (R) fatling (MKh)."

This interpretation gives the gist of the inscription, but work still needs to be done on refining the syntax and defining some of the terms; and there may be other more plausible ways of dividing the sequence of letters.

For example, Michael Sheflin's interpretation, involves Athtar and El; but that does not suit the context of celebrations for the goddess in the desert, though he acknowledges that this was apparently a place where such festive rituals took place; but he follows a number of false trails, and offers a roller-coaster ride of ups and downs in dating and interpreting. He does laudably make a single text from the two inscriptions.

Douglas Petrovich (The World’s Oldest Alphabet—Hebrew as the Language of the Proto-Consonantal Script, Carta, Jerusalem, 2016.) has publicised this translation of the horizontal text, which likewise has no connection with its environment:"Wine (yyn for wn!) is more abundant (rb) than (mn) the (h) daylight/dawn (ng), than (m) the (h) baker ('p), than (m) a freeman (h.r)". He would doubtless be able to explain infallibly the profound meaning of this poetry (something to do with the years of famine in Egypt? or the effect of the alcohol on the poet?), but it has several flaws to undermine it: the definite article is not active in the Bronze Age, so he needs to find other functions for the three cases of H (I would drop a speculation in here that the article ha, with doubling of the initial consonant of the noun it is attached to, derives from the demonstrative word han, having the -n assimilated; the Arabic 'al may be related to the Hebrew demonstrative 'el (plural); the analogy for "that" > "the" may already be in that English pair, but Latin "that/those" ille, illa, illos, illas developed into definite articles, il, le, la, los, las; the shining (ngh) must have its final aspirational consonant, and it is lacking here; his third "than" is not M but Th (thad breast); the underlying defect that brings his whole construction tumbling down, and falsifies his grand unified theory, is his stubborn insistence that the Hebrew Patriarchs spoke the language of the Bible, and no allowance is made for sound-changes over the epochs, such as wn > yn (which, according to Petrovich, must be written yyn, as in Biblical Hebrew).

With regard to the vertical line, he interprets the recurring sun-sign (Sh from shimsh, already as Shi in the Protosyllabary) as the Egyptian KA sign (|__|), for K; thus his entire reading of the text will be invalid.

Petrovich has included his faulty translations of several Sinai proto-alphabetic inscriptions in his second book: Origins of the Hebrews: New Evidence of Israelites in Egypt from Joseph to the Exodus (Nashville, 2021). However, the thesis of this monograph is worthy of our attention, and I am presenting my favourable response to it in my essay Israel in Goshen:

https://sites.google.com/view/collesseum/gebel-tingar-statue

DATING

What is the date of the inscription? If it is contemporaneous with the Sinai corpus it could be LATE BRONZE AGE or MIDDLE BRONZE AGE, though the Sh-sign (sun with uraeus serpent) is supposed to belong to the New Kingdom period (= LBA) not the Middle Kingdom (= MBA). See the note on V2 above. Nevertheless, the sun is sometimes portrayed in Middle Kingdom iconography with a serpent but without the tail. Therefore the evidence presented by Darnell (2005, 86-90, 102-106) is important, and it points to the reign of Amenemhet III (in the 19th century BCE). An example of this icon, matching the Sh-sign of our inscription (V2 and V11) occurs on an Egyptian stela from the turquoise mines (Sinai 84), dating from Year 4 of Amenemhet III, mentioning 10 Asiatics among the personnel of the expedition, and "the brother of the Prince of Retjenu, Khebded" (a candidate for the position of inventor of the alphabet). A better-preserved instance of this icon is on a stela (Sinai 87) from the following year of the same monarch (5); Khebded reappears, and is even depicted. There is no doubt in my mind that this version of the sun was the model for the unique Shimsh-consonantogram in the Hol inscription; and yet it is not found in the Sinai proto-consonantal texts, where the double-serpent icon without the sun-disc prevails. However, the suspicion is growing stronger that the proto-alphabet was a product of the time of Amenemhet III, in the 19th Century BCE, and the nobleman Khebded is a Western Semite with Egyptian cultural connections who could have been a promoter (and even the inventor) of the new West Semitic consonantal script. Orly Goldwasser is probably correct in surmising that Egyptian hieroglyphic writing inspired Western Semites in Egyptian territory to devise a new acrophonic consonantary; but they would not have been illiterate; they were conversant with their own writing system, an acrophonic syllabary, using borrowed Egyptian characters for its syllabograms, and they knew how the Egyptians manipulated their own hieroglyphic consonantary.

A summary of my interpretaion is published here:

COLLESS, Brian E., "Proto-alphabetic inscriptions from the Wadi Arabah", Antiguo Oriente 8 (2010), pp. 75-96, particularly 91-92.

COLLESS, Brian E. "The Mediterranean Diet in Ancient West Semitic Inscriptions", Damqatum 12 (2016) pp. 3-20 (esp. 5-6)

COLLESS, Brian E., "Recent Discoveries Illuminating the Origin of the Alphabet", Abr-Nahrain, 26 (1988), pp. 30-67. A preliminary attempt to construct a table of signs and values for the proto-alphabet, and to make sense of some of the inscriptions from Sinai and Canaan.

COLLESS, B.E., "The Proto-alphabetic Inscriptions of Sinai", Abr-Nahrain, 28 (1990), pp. 1-52. An interpretation of 44 inscriptions from the turquoise-mining region of Sinai.

COLLESS, B.E., "The Proto-alphabetic Inscriptions of Canaan", Abr-Nahrain, 29 (1991), pp. 18-66. An interpretation of 30 brief inscriptions from Late-Bronze-Age Palestine.

COLLESS, B.E., 1996, "The Egyptian and Mesopotamian Contributions to the Origins of the Alphabet", in Cultural Interaction in the Ancient Near East, ed. Guy Bunnens, Abr-Nahrain Supplement Series 5 (Louvain) 67-76.

COLLESS, B.E., 1992, "The Byblos Syllabary and the Proto-alphabet", Abr-Nahrain 30 (1992), 15-62.

And my other articles on the Canaanite syllabary ("Byblos pseudo-hieroglyphic script") in Abr-Nahrain (now Ancient Near Eastern Studies) from 1993 to 1998, culminating in:

COLLESS, Brian E., "The Canaanite Syllabary", Abr-Nahrain 35 (1998) 28-46.

All except 1988 are available at the Peeters website.

CROSS, F.M., Leaves from an Epigrapher's Notebook (2003). Collected articles

DARNELL, J. C., Theban Desert Road Survey in the Egyptian Western Desert, Vol 1 (Chicago 2002)

DARNELL, John et al, "Two early Alphabetic Inscriptions from the Wadi el-H.ôl", The Annual of the ASOR 59 (2005) 63-124.

HAMILTON, Gordon J., The Origins of the West Semitic Alphabet in Egyptian Scripts (Washington 2006) XVI +433 pages (Appendix 1, 323-330, Wadi el-Hol Texts 1-2)

SASS, B., The Genesis of the Alphabet (Wiesbaden 1988)

ZUCKERMAN, Sharon (1965-2014), "'.. Slaying Oxen and Killing Sheep, Eating Flesh and Drinking Wine..'; Feasting in Late Bronze Age Hazor", Palestine Exploration Quarterly 139, 3 (2007) 186-204. (provides bibliography on feasting and festivals)

" Behold, joy (sswn) and gladness (simha), slaying (hrg) cattle (bqr) and slaughtering (sht.) sheep (ç'n), eating flesh and drinking wine (yyn). Eat and drink, for tomorrow we die" (Isaiah 22:13)

This is my chart showing the development of the proto-alphabet. Wadi el-Hol letters

are on the far right of the Sinai-Egypt section. Click on it to see the enlarged picture.

![[S+383+drawing.jpg]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhdBd9t94mnLUlhhMjEO7LPmPq7R5L1MOgiKRaWiowPl6StaiW3qhKg4iAjN4aF3waPNIR-3tYaCpmMPnjmgul1pJnbuDU63b4Fug6hEAsuKjO4UZZ7TtUJs9eym3ZOitp9y2qiiw/s1600/S+383+drawing.jpg)